What It Means to Domain-Drive Your Design

I’m currently reading Object thinking by David West to get more general input on object-oriented programming. So far, it seems that most of the cool stuff I discovered for my coding practice in the past years is actually ages old. (Of course this is my interpretation, based on my current knowledge, re-producing and re-discovering expected results in new words.)

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) helped me solve software architecture problems. I really like the methods and patterns from there. Now David West tells me that the fundamental advantage I saw in DDD is actually fundamental object thinking.

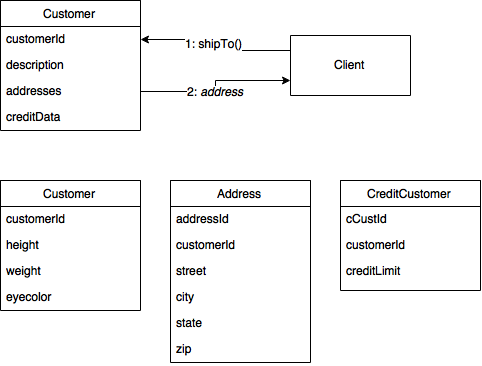

Here’s his example:

When you think in terms of objects and the problem domain, then you will model entities which can answer real business questions, like: “what’s the shipping address for this order of customer X?” – That’s what the top interaction depicts.

If you center on data, you will normalize the representation (of a SQL database, say, which is tables) into multiple data structures. But how do you find out which address to use? If the customer has multiple addresses, the information about which one to choose has to be encapsulated somewhere.

That’s the difference between focusing the problem domain and the solution space. The solution space is all about thinking in terms of the computer. The problem domain makes you understand what exactly has to be modelled, in a way that’s actually intelligible.

If there were just data structures, there’d have to be a free-floating algorithm to pick the appropriate address.

With objects, you have the option to create super-high cohesion of these concepts and encapsulate both in a Customer object.

Now DDD has taught me that any given object is only valid in respect to its context. If a large business has a shopping website, “customer” will mean something different in this e-commerce context than it does in the context of shipping. Logistics will in turn not need to know anything about the purchase history of a customer while the marketing department can totally use that.

In my Mac app Word Counter, a word count means different things in different contexts, too. There’s word counts of a file’s content, and there’s the amount of words typed into an app tracked over the course of the day. They don’t work well together and represent different things.

I’m going to write more about West’s book once I finished it. So far, it’s a very nice read. He’s a good technical author.