Coding TableFlip: the Bigger Picture

Now that TableFlip is nearing completion, I want to share details of how I created this piece of software with you.

Today, I’ll start with the bigger picture: the application architecture.

Starting with ReSwift

Earlier this year, I got to know ReSwift from a talk by Benjamin Encz which I loved.

I got in touch with the team and contributed a bit to the codebase myself. To get a feeling for it, I created a still unfinished sample To Do list app. (I’m going to finish the app for the course of a small book on ReSwift this year, don’t worry guys!) When I started to work on TableFlip I leveraged my knowledge of ReSwift to give the approach a real world pressure test.

So I started the app with ReSwift in mind. ReSwift doesn’t impose external constraints to the development process that really matter. ReSwift takes care of keeping the app state consistent and to model the flow of information properly. That’s a huge win.

Ditching ReSwift later won’t hurt your code much, though: ReSwift doesn’t dictate an approach to software architecture. It simply takes care of passing data around and maintaining a consistent overall app state.

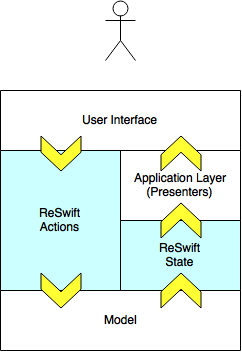

ReSwift became the kind of glue that holds moving pieces of TableFlip together. To make sense of this weird metaphor, let’s have a look at the overall app architecture first.

Application Architecture

The app’s architecture is not affected a lot by ReSwift. ReSwift takes care of event dispatch, but only in a very small portion of the code base. In terms of process, it’s a central piece of logic. In terms of creating the parts or structure of the app, ReSwift’s portion is negligible.

The App’s Heart: the Model

When I started to develop TableFlip, I started what I believe to be the most important part: the model.

It’s most important because it encapsulates all core rules to the “table flipping” domain. It is a model of the problem domain: editing tabular data with multiple sheets in a single document. Tables can be resized; tables can be removed from the document; table cells can be edited and moved. These are only a few of the foundational pieces from the problem domain. When these are modeled well, creating a Cocoa Mac app on top of it is a piece of cake.

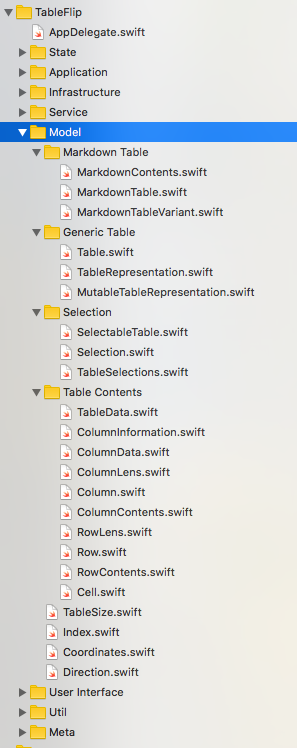

TableFlip’s model is very expressive on the inside while exposing a simple interface to the rest of the app. I won’t go into detail for every piece of code I wrote. Here are the most important protocols and some primitive value types for a brief overview:

TableRepresentationis a protocol that defines how you can query something forCells at specificCoordinates, for example. It exposes the overallTableSize.MutableTableRepresentationis an extension toTableRepresentationand provides means to overwrite cell data, insertRows andColumns, and resize the table.SelectableTableis a protocol that exposes info about whichCells in a table are selected; moving or expanding the selection into aDirectionis possible, too.Tableimplements the table representational protocols andSelectableTable. It’s the foundational

The value types I used are probably the most powerful part:

Coordinates are provided as pairs of Indexes. An Index is an unsigned integer under the hood, restricted to values of 1 (not 0!) and above. With these I don’t have to worry about illegal coordinates like (-1, -1) because the types I use don’t allow those.

In other words, instead of defensive programming I encapsulate rules in types. With guarding against illegal values throughout the app a similar effect could have been achieved. It would have come at a high cost, though, spreading business rules all over the place. Instead of replicating the guard statement wherever necessary, I use types that incorporate all the knowledge and make my app a lot more robust.

Index is also a ForwardIndexType so I can create collections based on them. Another place where I don’t have to worry about special conditions – I simply employ the Index type as the collections index and can have piece of mind.

So a Table object is really at the core of everything. You ask it for data with Coordinates and query for rows and columns by Index; overwriting cell data happens through passing a NewCell object in. The Table takes care of everything else. It manages its boundaries (literally, too: it doesn’t insert data beyond the TableSize) and “client code” can rely on it working correctly. On top, there’s tons of unit tests to verify I don’t break anything.

Editing CSV files solely depends upon manipulating a single Table instance and persisting its state. Easy.

The Markdown-related types are a bit more intricate. A Markdown file can have multiple tables in it with regular text in between. So I have added MarkdownContents to represent a Markdown file. It is made of MarkdownParts, either .text or .table, to represent a sequence of content sections. When you save the Markdown file in TableFlip, you expect the text contents to stay intact, so I have to keep these save.

Also, a MarkdownTable can come in many variants: no surrounding pipes at all, leading pipes, trailing pipes, and pipes both at the beginning and end of the line. Thus a MarkdownTable is not much more than an adapter for a regular Table with a few extensions.

If I were to write a command line application, the model would be able to represent the file contents. All I’d need is some way to import and export file data. The model is the mutable representation of the tables itself. It adds a meaningful layer of abstraction to “adding text and pipes to a string in a file”. Instead of operating on the text level and counting characters, a Table helps the developer to express her thoughts in means of insertRow(above:) and changeCell(at:, contents:).

Import and Export

The model already sports behavior. You can add, move, select, delete and insert stuff. That’s a language which makes changing tabular data easy. Coming up with and realizing such a language arguably is the only job we programmers really have. The rest is adding user interface chrome and algorithms to realize use cases.

TableFlip to me is very much centered around file operations: opening Markdown files, changing stuff, then saving back the changes. So the first layer around the model is file I/O: importing and exporting CSV and Markdown files.

Parsing CSV is piece of cake. There’s some kind of delimiter (tab character, comma, semicolon, whatever) and each row has its own line. Read and parse the file, create a Table from it, and you’re done.

Parsing Markdown files is a bit more cumbersome: you have to skip non-table content until a line appears that could be part of a table. When the table ends, you have to collect all the Markdown that follows until the next table begins (or the file ends). As I said above, tables come in different variants, too:

No | Pipes

at | all

| Leading | Pipe

| on each | line

Trailing | Pipe |

on each | line |

| Surrounding | Pipes |

| just | everywhere |

Once finding out when a table starts, how long it continues, and deciding of which variant it is, you’re set. It’s still not a lot of work but error-prone. Again, unit tests and file-based fixtures to the rescue.

The User Interface on the Outside

Until I write really complicated applications, I simply architect them in layers. The model is at the core with all its business logic. Naturally, the user interface is at the outside. In terms of user interaction, this is as far away from the core as it gets. One step further and you’d bypass everything AppKit or Cocoa offers, dealing with hardware signals directly. No, thank you – this is how the operating system enables the user to manipulate the application, so it sits at the boundary of the outside world for me.

I use Interface Builder and AutoLayout for creating the visual representation of a document window. There’s buttons, menus, and a table. Utilizing the responder chain is helpful to centralize handling of interactions. I won’t go into much detail on handling UI events here.

When the Cocoa NSView components the user sees on the screen are the outer edge, then dispatching events the app understands is the inner edge. In between is all the view setup and view controller stuff.

The kind of events the user interface layer emits are ReSwift-compatible Action types.

So ReSwift is the ultimate translation of UI interactions to events that change the app’s state. This in turn is using the model. The altered model then is pushed to observers. One of these is the Presenter which tells the view to update itself with a view model that is derived from the new state.

The Ominous Application Layer: Glueing State to the View

In TableFlip, there’s not much need for a traditional “Application Layer” that takes care of responding to events. If I weren’t using ReSwift, I’d write event handlers in this layer between UI and model. This is what makes the particular app what it is, for example:

- either a shell program (writing text to stdout),

- a Cocoa application (orchestrating display of AppKit windows),

- or a server (assembling JSON and sending it off to clients).

Since both the UI and model are self-contained, merely NSDocument subclasses and a TablePresenter live in this layer.

Because there’s a portion dedicated to ReSwift state updates elsewhere, the presenter takes care of view updates through protocol it owns. It’s so simple I show its public interface to you in full:

protocol DisplaysTableDocument {

func showTableDocument(viewModel: DocumentViewModel)

}

protocol DisplaysTable {

func showTable(viewModel: TableViewModel)

}

class TablePresenter {

typealias View = protocol<DisplaysTable, DisplaysTableDocument>

let view: View

init(view: View) {

self.view = view

}

}

extension TablePresenter: StoreSubscriber {

// ReSwift state observation entry point:

func newState(state: DocumentState) {

let documentViewModel = self.documentViewModel(documentState: state)

let tableViewModel = self.tableViewModel(documentState: state)

view.showTableDocument(documentViewModel)

view.showTable(tableViewModel)

}

private func documentViewModel(documentState state: DocumentState) -> DocumentViewModel {

/* 10 simple lines of logic */

}

private func tableViewModel(documentState state: DocumentState) -> TableViewModel {

/* Another 8 lines of logic */

}

}

Notably, the Application Layer defines the protocols a compatible view has to implement. Not the other way around. The presenter does not depend upon the view; the view has to meet requirements of the application instead. This helps to hide details of the UI and prevents me from reaching deep into window controllers and the like. They have to take care of everything themselves once they receive a view model.

In other words I am inverting the dependencies for cleaner boundaries between layers and in turn achieve relative independence of the application from the view layer.

This approach would make it possible to write multiple views and create different app targets, each with its own view implementation. The standard example is a terminal application VS a graphical user interface app. That doesn’t make much sense in my case. But if cross-platform Swift truly takes off, I can write a Linux and a Windows front end to the app simply by plugging-in a new view incarnation.

Conclusion

I employed a layered architecture approach – because I knew that I wanted to separate the model from the view cleanly, and because overall app state transitions with ReSwift are independent from the rest of the code anyway. These two isolated layers, model and view, made putting the rest into place very easy.

I don’t think twice if I should write clean code. That’s about the only ideal I always try to meet. From there it follows that sub-components, modules, or layers of my app on a macro-scale should themselves be “clean.” Whatever that means in the end – the intention is the same with every project I take on.

Among the benefits of clean layer boundaries, simplicity of interaction between layers is very important. If the view is tightly interwoven with the model, there hardly is a clean boundary. If the view exposes how it will encode user interactions as events and if the model exposes a public interface to perform changes, you only need very simple glue code to translate one to the other. The “glue” has to know both interfaces. View and model don’t have to know each other at all, though.

If something in the view is broken, I know where to look and which part of the code I can ignore. If the model doesn’t do what I intended, it doesn’t matter if the event originates in a button click or a direct method invocation from a unit test; I know where to look for faulty code.

Separation facilitates isolation; isolation facilitates clean thinking and in turn increases maintainability. You don’t have to think about the app as a whole but can focus on its sub-systems instead.

The benefit of cleanly separated layers is that their boundaries increase cohesion inside the layers and help not create a mess of everything. A model object should never need to know anything about how a NSView works, so when you perform changes on model code, you can forget about AppKit (or UIKit, respectively) for a while. It’s only the tiny world you created that matters.

Most of this is targeted at keeping code readable. Writing an app is not a “write once” think. You constantly have to revisit old code. If it is highly cohesive, you can tweak it more easily.

On top of all that, the separation enables me to rewrite parts of the application with ease. Like I said, a Linux UI or maybe an iOS app would simply require coding a new view layer, that’s all.

Layered architecture is a very simple approach to application architecture. There’re others, more complex approaches. I found layered architecture to meet my needs to isolate and solve most of my day-to-day problems, though.

I spend a lot of time with the initial model design. Once I was ready to dive into file I/O and then try to implement a NSDocument subclass, the model was further refined to meet real-world problems I didn’t think of initially. I wouldn’t ever call the model finished. That doesn’t make sense. The app as a whole is constantly improved.