Iteratively Improving Your App: Decoupling Components at Module Seams and Adding Facades

Façades are very important tools when I flesh-out the modules of an application. They turn out to be only the logical consequence of basic object-oriented programming principles, internal cohesion of objects namely, paired with decoupling of application modules (like “model” and “view”).

Take a complex view that has many subviews. When you need to update a single piece of the user interface, how do you get there?

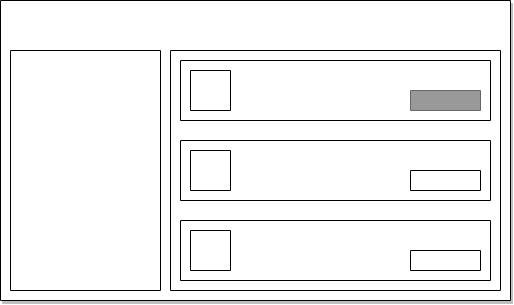

Take a common split-pane application, no matter if it’s on Mac or iOS. There’s some button or label in the right detail pane’s table view’s first cell. I want to change its label and adjust its state to “enabled,” say. I highlighted the widget in question with a grey fill in the diagram.

Again, how do I get there? (How would you?)

Let’s explore this iteratively so you see why I end up with the solution I usually do.

Extract the subview update responsibility

One of the first attempts might be this: you create a Presenter for that part and wire it to the specific view component. Maybe put the presenter into the Storyboard or Nib so you don’t have to worry about its creation programmatically.

When data changes, you tell the presenter to updateView(_:) with new contents and it takes care of the rest. It’s a pretty simple setup: a one-to-one connection from a controller object to a view component object.

A presenter would be part of the applications control mechanisms; it is itself not part of the user interface layer. It controls the view, it is not itself a view.

Since a presenter is a POSO (Plain Old Swift Object) and doesn’t depend on any AppKit or UIKit types like UIViewController, it’s easier to reason about its role in all this. For some people it makes sense to say that a UIViewController subclass is itself a view; others insist the term “controller” implies the opposite. (I’m in the former camp.) A custom presenter type doesn’t have this problem, so we don’t have to argue.

With this seemingly innocent approach, you have wired your application control structures deeply with the user interface layer, though. They have coupled tightly.

Looser coupling promotes flexible designs: you are able to change stuff only when modifications don’t ripple ripple through all of your app. If they do, making changes is going to suck. If changing stuff sucks, you will not want to improve the code. Or add features. Not good.

So a 1:1 presenter–view connection can help to push UI updates but couples the two very closely.

Next step: apply some “decoupling”, whatever that means.

Decoupling dependencies

We can “decouple” things on multiple levels. Objects can be coupled. Modules of the app can be coupled. Overall app and 3rd party frameworks can be coupled.

The cure is to insert abstractions as buffers. I’m going to show an example and then explain the benefit.

Decoupling on the micro or object level can be achieved through abstractions to interfaces—protocols in our case as Cocoa developers. Defining a protocol for the Presenter’s view component will help a bit. It will not go all the way, though, as we’re going to see. But it’s a start:

protocol DisplaysBanana {

func showBanana(bananaViewModel: BananaViewModel)

}

class BananaPresenter {

typealias View = DisplaysBanana

func updateView(banana: Banana) {

// create banana view model & show it

}

}

This is an improvement for two abstract-ish reasons I’ll try to make more concrete in a second:

- You can change which class in your UI layer will implement the protocol.

- You can hide details of the concrete implementation from client code, in this case: the presenter.

I admit: The first reason is strange. It’s not very likely you want to switch an ABCViewController for a XYZViewController once you got this far. This kind of flexibility is faux flexibility.

There’s a point, though. When the concrete implementation is unknown to the caller, you don’t have to change the BananaPresenter’s source code when things change in the UI module. The presenter’s module dictates what the protocol is like.

The real benefit is hidden in the 2nd reason. The Presenter doesn’t know anything else about the concrete view object it interacts with except the things the protocol dictates. So the Presenter’s “module” is in control.

Before decoupling the objects through a protocol, the Presenter and a concrete View type were coupled through mutual dependencies. The arrows in the above diagram indicate who is controlling whom. The view implemented an showBanana(_:) method as part of its published interface (accessible to callers). The Presenter depended on this method to work. If you change the view to work differently, you’d have to change the presenter, too. This is a kind of control. On the other hand, the view cannot do anything without receiving data in the first place. So the presenter kind of has a veto through not using the method at all, while the view dictates how things are going to work.

After introducing the protocol, the presenter’s module dictates what the contract really is like. Whatever object is used to display stuff: it has to adhere to the rules the protocol imposes. It’s not the presenter itself who dictates the rules. It’s the presenter’s module. The “stuff that shows data in the UI when data changes” module. I like to call it “the Application layer.”

We have inverted the dependencies. Instead of the presenter relying on the view type directly, their connection is mediated. The protocol is effectively a buffer. When the protocol changes, the view has to change, too. But the view can change independently as much as it wants as long as the contract is still satisfied, as long as updateView(_:) is still implemented.

Simply put, we can change the view to our liking and refactor like hell and the compiler will help us not break anything or accidentally affect dependencies. And looking from the other side, our presenter’s controller code can never reach deeply into the concrete view’s object graph and increase coupling.

You know how sometimes it’s just too easy to violate boundaries, reach deeply and call something like viewController.someLabel.text = newValue? It’s impossible now because the presenter doesn’t know about someLabel being present. (You could conditionally cast from DispaysBanana to ConcreteBananaViewController, of course, but that’d be stupid and the stupidity clearly shows in code.)

Now that on a micro or object scale the decoupling is sufficient, step back once more. If you have N view components, it’s not feasible to create N presenters, each with its own view protocol. Although the initial design of MVC did exactly that, I find this approach very cumbersome. You’d create a useful buffer layer of abstractions between (Presenter_1...Presenter_N) and (View_1...View_N). But the amount of connections can become overwhelming and hard to maintain, too.

That’s where next-level decoupling comes into play.

Simplifying the dependency graph through Façades

The complexity of dependencies can explode with a complex view and one presenter for each of them. It will be maintainable. It will not be easy to wrap your head around things, though, and instead of adjusting how the objects work you’re probably going to replace them entirely because they are so super-focused. That’s not a bad thing, mind you. I think there’s a more scalable way.

I picture the problem of having N views, N presenters, and N view–presenter-connections to look like tons of cables on a desk, one from each device into the computer. The cable problem can be simplified through a bottleneck, like USB hubs and cable canals. Voilá, the mess is gone.

A Façade is a Design Pattern that does just that. With it, we can take the decoupling even further by abstracting away the multitude of objects and hide them behind a single interface.

Thanks to the view protocol abstraction, the facade can be introduced as another mediator:

class ConcreteBananaDisplay: NSView /* or UIView */, DispaysBanana {

func showBanana(bananaViewModel: BananaViewModel) {

// view setup logic here

}

}

class BananaFacade: DisplaysBanana {

@IBOutlet var bananaDisplay: BananaDisplay!

func showBanana(bananaViewModel: BananaViewModel) {

bananaDisplay.showBanana(bananaViewModel)

}

}

The presenter is wired to the Façade object which then delegates to affected sub-components. It hides implementation details (“which object does what?”) from the outside world, whereas “outside world” in this case means “every other part of the app that’s not in the UI module”. With this approach you promote decoupling of modules in your app.

Say you have even more fruit, see how this is scaled:

class FruitFacade: DisplaysBanana, DisplaysApple, DisplaysOrange {

@IBOutlet var bananaDisplay: BananaDisplay!

@IBOutlet var appleDisplay: AppleDisplay!

@IBOutlet var organgeDisplay: OrangeDisplay!

func showBanana(bananaViewModel: BananaViewModel) {

bananaDisplay.showBanana(bananaViewModel)

}

func showApple(appleViewModel: AppleViewModel) {

appleDisplay.showApple(appleViewModel)

}

func showOrange(orangeViewModel: OrangeViewModel) {

orangeDisplay.showOrange(orangeViewModel)

}

}

Sure, the repetition gets kind of boring. But this component now is the bottleneck where all view updates will go through. It’s one single place to worry about.

For that matter, the sub-components wouldn’t even need to implement the various view protocols: since they are not passed to objects outside the UI layer, nobody cares about their protocol conformance anyway. The Façade could do things in entirely different ways behind the scenes and nobody will notice. As a personal preference, I tend to make both the Façade and the object it delegates to implement the same protocol to show through protocol conformance which view component is designed to fulfill a certain purpose. But you don’t need to.

Real Life iOS/UIKit Application

On iOS, your problem view could be a UITableView. The design of UIKit encourages you create a Façade without thinking twice about it: a UITableViewController. When data changes, you pass it to the view controller, not to the table view directly. The view controller takes care of configuring the table’s cells.

This whole design is based on a lot of indirection: you don’t push changes to the UITableView. Instead you tell it to reload itself so it fetches missing views from its delegate and the contents from its data source. The UITableView doesn’t care which object in your app implements these protocols. Traditionally, you use a UITableViewController for this. But it could be any POSO, anywhere in your app, as long as you wire the table view to it.

A UITableViewController hides implementation details of its table: how cells are set up and what they look like.

I bet your view model will resemble a sequence or collection, most prominently using arrays. But you don’t have to make model data respond to UIKit’s UITableViewDataSource needs. The view controller does that. And so the app’s glue code worries about setting up a proper model for the view controller, not about the table view.

OS X/AppKit Specification

Let’s say there’s a NSDocument based app with a window open that shows the split pane from above. The window has NSOutlineView to the left and a content pane to the right, ultimately including a NSTableView. Let’s say you use it to edit items in projects, much like Xcode, for example.

Now the project data changes under your feet because the user deleted a file on her disk and your app receives a notification and updates the data. Instead of reaching to the outline view directly and replace the list, you tell the document or its window to showProjectItems(_:). It then delegates to its outline view appropriately. If the currently viewed item was deleted, this will also take care of clearing the detail pane to the right.

Programming for OS X, I often find a window to be the best candidate for Façade. It contains all sub-view controllers anyway.

In fact, the Word Counter’s menu bar panel is the Façade for 3 NSViewControllers, each with their own Nib. They in turn are a Façade for the actual NSView components that display stuff: table views, labels, buttons, and charts. Isolation of modules and components all the way down.

This way you let the view module achieve inner consistency and coherence for a meaningful change. The alternative is to reach into the view module with controllers and replace the outline’s contents in one step and worry about the detail pane in another. Then the coherence criteria are exposed to the controlling objects. Thus the view module is opened up to being manipulated in a way that results in an inconsistent view state. So you have to add even more checks and tests to the controllers and dumb down the view components themselves.

View components should be dumb inasmuch as they should not know anything about real business logic and how to process network requests, for example. But they can be smart enough to care for themselves.

In a nutshell

“Smart enough” objects is the whole point of object-oriented programming: object boundaries are used to maintain consistency on the inside. State is encapsulated and objects expose methods to perform meaningful change. If you don’t do it that way, you create mere data containers and end up with all the logic in one place, most notably view controllers, which then overwhelm you with their intricate complexity.

Decoupling reduces complexity by keeping object boundaries intact: strong coupling forces you to think about all objects involved. Clear separations through protocols as interaction contracts help you to reason about an object and what it does.

More objects isn’t better to grasp where information flows per se, because a multitude of cleanly separated objects is still hard to hold in your head. That’s where designing bottlenecks comes into play, for example as Façades. All of this makes sense with objects that are autonomous only, or you’ll end up with train-wrecks like facade.subcomponent.detailView.label.text and wouldn’t gain a thing.