Framework Oriented Programming and It's Relation to OOP

frameworkoriented.io hosts a text on “Framework Oriented Programming” (FOP). That title already looks similar to “Object-Oriented Programming”. But it’s not a replacement, mind you; it surely means the same for our cause as Cocoa UIKit/AppKit developers. The shift in perspective from object to framework works very well to illustrate the problem of designing large code bases.

Libraries (or “frameworks”) are possible thanks to object-orientation. OOP made code re-use a reality. Now FOP’s point is to make this a standard mode of writing apps: write libraries for the parts of your app and integrate them in an application target to keep your code maintainable.

The bottom line of all this is: draw boundaries and stick to them. Don’t cheat. Don’t go the easy route and mix responsibilities; take your time to design your app’s components to be separated and well-factored. Put your view controllers on a diet. Stuff like that.

This is an old hat so far. So how’s “Framework Oriented Programming” providing new insights?

Frameworks are a way to draw boundaries. Through the nature of separate compilation, these boundaries are very strict. Frameworks need to be fully self-contained or else they won’t compile. They may depend on other frameworks, sure. But they can’t be missing pieces.

Object-oriented programming is all about boundaries. You draw object boundaries through creating types and providing methods as the published interface of said type: as the well-controlled passageways across the boundary.

But with objects you can always cheat if the visibility of the properties allow direct access, for example. Want to circumvent the tons of checks for validity that are performed carefully in complexThing.integrateOtherThing(_:)? Why, just access complexThing.children.append(_:) directly for convenience! Then suddenly your code degrades because complexThing cannot guarantee its integrity anymore. (“That was whole purpose of an Aggregate object like this – and some idiot just made it worthless,” you might cry in frustration. Rightly so.)

Frameworks are drawing boundaries on another level. They do so in a much stricter fashion and enforce rules than objects in a single code base alone won’t be able to.

Objects and frameworks do not relate to each other like part and sum; it’s a more complex relationship. We can generalize and use the term “module” for both object and framework and find out that there are even more levels. I found the term “module” can be used for these partitions at least:

- statements;

- functions;

- objects;

- object groups (“modules” in a colloquial sense);

- frameworks;

- applications.

In the end, it boils down to justifying why you drew boundaries in some places and not others.

What’s the boundary of an object? Why does it do X but not Y? – There’s no one true answer. It’s arbitrary. But through justification your decisions become design. That’s when through reasoning and argumentation you create meaning from arbitrariness.

You can aid finding answers to object-related design questions through trusted principles. Take the Single Responsibility Principle as a guiding design heuristic and you will be able to tell why an object should not also do Z: because then it’ll do multiple things with low cohesion, thus rendering the purpose of the object type incomprehensible.

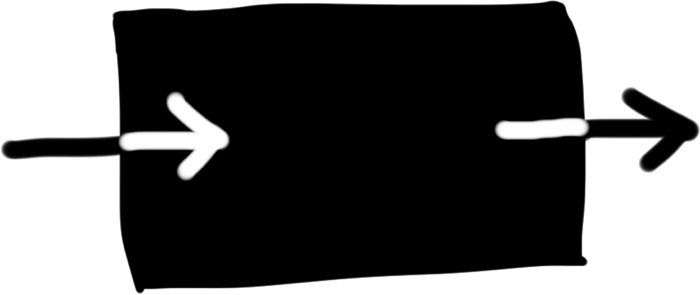

A module in each level should be a black box with high cohesion: the concept of a black box unifies the whole of software modeling, it seems.

The metaphor of a black box is so general that it’s nearly meaningless and I always found it to be pretty useless in practice until recently. Turns out it summarizes a lot of specialized principles like the Single Responsibility Principle nicely and shows a unifying principle.

A black box is characterized by:

- a boundary

- input

- output

The I/O part is obvious and most people stop there; but the boundary part is even more important. It can be applied to “modules” on all levels of abstraction. Taking the general terms “black box” and “module” on their own is only theory; you need to re-specify “module” and apply the concept “black box” to take away something useful:

- Objects have boundaries. They have a published interface that other objects can use to send commands (probably performing state changes) or query for information. Other objects may also hook up as delegates and realize the output port.

- Frameworks can work in a similar way:Protocols define how client code can hook into a framework as an output port; model objects define how clients are supposed to provide data.

A framework takes care of all that to keep its internal cohesion high and be fully self-contained. A framework tells the client how it wants to be used. Client code will not know – and will not need to know – what’s going on behind the scenes. That’s the strength of high cohesion and crystal clear boundary definitions.

All the while, a boundary is not something you define separately. It is the result of publishing the possible modes of interaction. If all a framework provides is 1 public delegate protocol, 1 setup function, and 1 accepted data model in 1 command function, it’s easy to see how you’re kept outside of the framework’s internals so it can maintain integrity. Thus the framework reveals its boundary. During creation, the boundary emerges from your design decisions. – And if you do your job badly, the boundary will be hard to grasp.

Here’s a variation of Murphy’s Law I just made up: every method that can be called, will be called.

Be as restrictive as possible. Design bottlenecks of control flow and find ways to reduce the possibilities of doing stuff. Then your future self or your team-mates won’t be lured into the dark side of writing messy code.

This, in turn, is the reason why global variables are “bad”: because you can use them from anywhere without penalty (at least not while you write the code; you will get hurt later, when runtime issues arise). Humans generally don’t exercise high will-power and discipline. Some day some line of code will magically turn up and exploit what can be exploited just to save time coding.

Hard boundaries make misuse next to impossible if they are designed well. This is the strength of partitioning your code base into multiple framework targets. It will make things that are “bad” harder to do while you want to do them. It’s more like Minority Report’s preventive arrests than punishing misbehavior after the fact. Setting things up this way means you will spend more time properly separating components up front, though. The reward will be visible much later, when changes in one place are well-contained instead of rippling through your entire code base.

So when you create your next app project, try adding a framework target directly after the initial commit and start from there. You may learn something about OOP, after all.