Zettelkasten for Programmers: Processing Swift Actor Usage Advice in Depth

Matt writes about concurrency, the world listens. So do I – and from his recent article “When should you use an actor?”, I created a couple of notes and quickly wanted to show you how I do it, why I do it this way, and what you could take away from this.

So first you may want to read, or skim, Mattie’s article.

Cursory Read

The article is phrased as a question, so one goal is to find the answers: when should you use an actor? Always keep in mind the opposite, approaching an answer through inversion: when shouldn’t you?

It contains a handful of short sections; each about a page full (at 133% zoom at least, which I’m apparently reading at). They are titled:

- Value vs Reference

- Quick refresher

- Actors

- Synchronous accesses

- Questions

- Why not MainActor?

- Actor justification

- Footnote: Sendable Protocols

I highlighted in bold the sections that sounded the most promising. I read everything anyway – but form a cursory glance, I actually found this high-level structure doesn’t fit my expectation to get to an answer to “When should you use an actor?” It’s certainly not for synchronous access, so the section titled thus is probably approaching the answer from the negative side. “Actor justification” may contain a direct answer, but in the context it sounds different than “7 reasons to use an actor” for sure.

What I take away sub-consciously from a quick scroll over the text is that I need to skim it and can’t just skip to a conclusive part. I don’t spend minutes on this step, but mere seconds; for explanatory purposes I’ve reflected much more on this than I would usually do.

So let’s hunt for the meat of the post.

Diving In

From the cursory first glance, my eyes locked on “Why not MainActor?” and the inline code highlights as information scent. The inline code markup is colorful, while the rest is black-and-white. That alone guides the eye, so I looked.

From that section I took away this in a new file, 202509160703 (a date-time-stamped note I created on 7:03), without a title:

In practice, programmers reach for stateless `actor`s in Swift to

express "this should never run on the main thread".[#20250916actor][]

- `async let` introduces a suspension point for background work just

as well, and simpler[#20250916actor][]

- `@concurrent` function opts-in to run on the concurrent thread

pool[#20250916actor][]

[#20250916actor]: Matthew Massicotte: "When should you use an actor?", 2025-09-06, <https://www.massicotte.org/actors>

Today, I also read the Swift 6.2 announcement post. That post also mentioned the @concurrent annotation in the context of Swift Approachable Concurrency, so I went ahead and created a note for that so I have a representation of this annotation in my Zettelkasten:

Note on Markup: The

[#20250916actor]thing is a citation, not a link; I talked about this in 2013 on this blog in context of reference management, now moved to https://zettelkasten.de/posts/bibliography-zettelkasten/.

# 202509160705 Run @concurrent in default MainActor isolation mode

#mainactor #concurrency #approachable-concurrency

Holly Borla's Swift 6.2 announcement post example for Swift

Approachable Concurrency illustrates how regular functions and async

calls will still be isolated on the main actor, but `@concurrent`

allows scheduling on the globalthread pool, which was the old default

behavior[#swift62][]:

```swift

// In '-default-isolation MainActor' mode

struct Image {

// The image cache is safe because it's protected

// by the main actor.

static var cachedImage: [URL: Image] = [:]

static func create(from url: URL) async throws -> Image {

if let image = cachedImage[url] {

return image

}

let image = try await fetchImage(at: url)

cachedImage[url] = image

return image

}

// Fetch the data from the given URL and decode it.

// This is performed on the concurrent thread pool to

// keep the main actor free while decoding large images.

@concurrent

static func fetchImage(at url: URL) async throws -> Image {

let (data, _) = try await URLSession.shared.data(from: url)

return await decode(data: data)

}

}

```

[#swift62]: Holly Borla: "Swift 6.2 Released", 2025-09-15, <https://www.swift.org/blog/swift-6.2-released/>

That’s a lazy start to represent the concept, but I don’t want to fall down into a rabbit hole that takes me on an hour-long detour. I’m in the middle of reading Matt’s article, and this is good enough to represent the concept in some form.

So mentally, I ‘stack unwind’ and exit this context with the new note about @concurrent in hand.

I’m not a computer, so returning to my note about Matt’s post is not lessless. I need to recapture some context. But first, I insert a link to the new concept – so now I have this as the second bullet:

...

- with Swift 6.2 approachable concurrency, `@concurrent`

function[[202509160705]] opts-in to run on the concurrent thread

pool[#20250916actor][]

...

(At the end, I’ll link to all notes in their final form, so you don’t need to keep track of diffs.)

A forward link to connect to the new concept, and mentioning “Swift Approachable Concurrency” explicitly as a term – this helps prime me a bit when I stumble upon this note again, and also helps with full-text search. I often find in programming and writing that it’s better to be verbose: brevity has its place, but it makes expansion and discovery harder.

Instead of a rock-solid diamond that’s forever unchanging, I want my notes to be malleable, form-able. More like clay.

Now Actually Reading the Post

So this detour took me a couple of minutes to read and assemble. The section “Why not MainActor?” seems to be exhausted, and I need to refresh the context anyway, so I now check the post from the beginning.

I skim the first two, three sections to check whether there’s anything that looks new to me. Even though I knew the stuff, it’s great Matt included this to prime the reader for what’s next – also: just in case the reader disagrees or is confused by conclusions, the introductory sections are there to bring them onto the same page of baseline assumptions.

Then “Synchronous accesses” got interesting – by conceptual opposition to ‘asynchrony’, it stands out anyway; and it contains this gem:

In fact, I think it can be quite useful to think of an actor as a remote network service. Its data is physically inaccessible to your process, off on some server somewhere. You must make a network request to interact with the system. Inputs to your request must be packaged up and sent (💡… Sendable?). The same goes for the system’s responses. Other requests to the system could be happening at the same time.

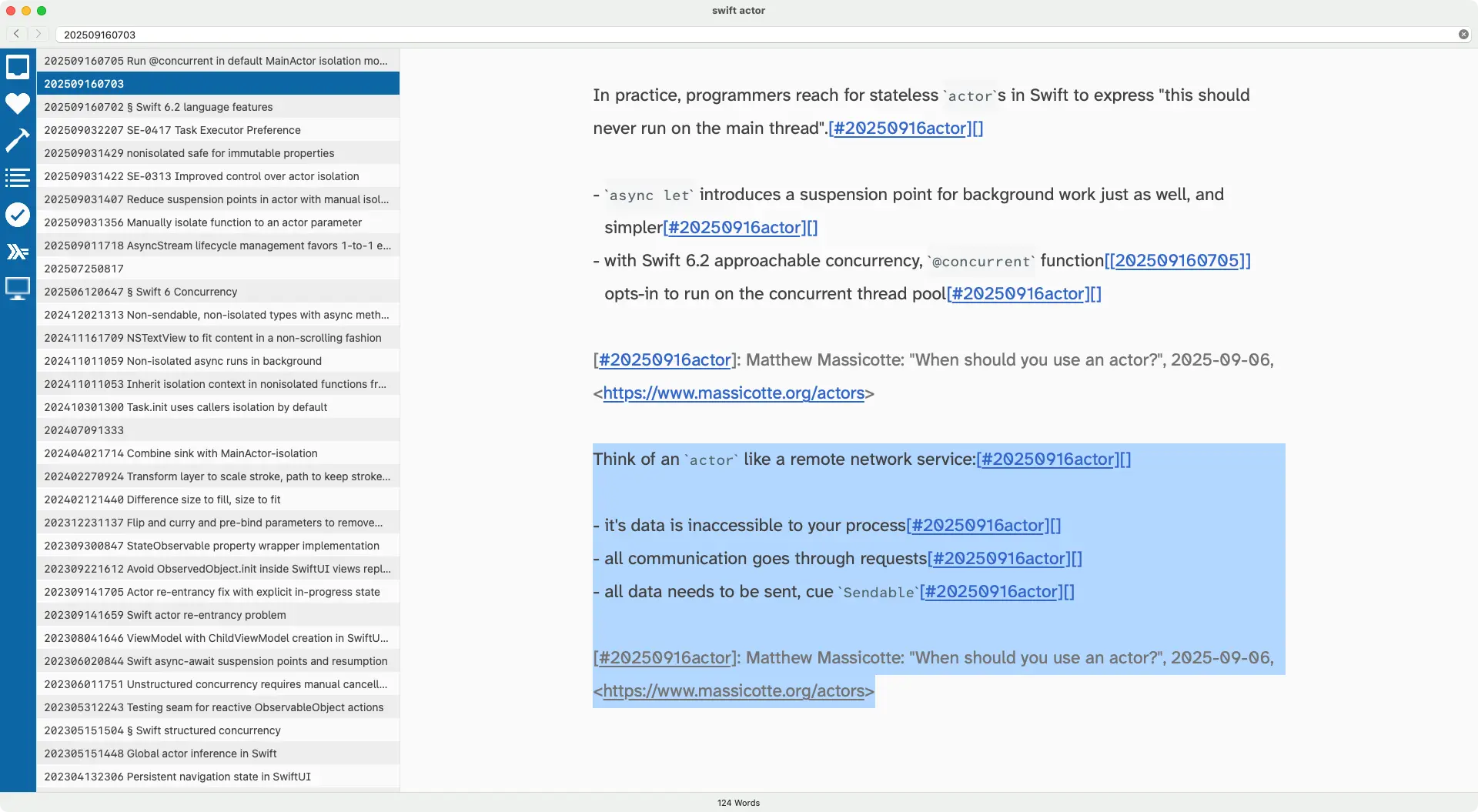

I love that metaphor, and it’s new to me, so I want to have it in my toolbox. I’m capturing it right where I am, because it’s from the same source, so extracting it later from here will be simple. I duplicate the citation in the end for cut-and-paste refactoring, and now have this:

In practice, programmers reach for stateless `actor`s in Swift to

express "this should never run on the main thread".[#20250916actor][]

- `async let` introduces a suspension point for background work just

as well, and simpler[#20250916actor][]

- with Swift 6.2 approachable concurrency, `@concurrent`

function[[202509160705]] opts-in to run on the concurrent thread

pool[#20250916actor][]

[#20250916actor]: Matthew Massicotte: "When should you use an actor?", 2025-09-06, <https://www.massicotte.org/actors>

Think of an `actor` like a remote network service:[#20250916actor][]

- it's data is inaccessible to your process[#20250916actor][]

- all communication goes through requests[#20250916actor][]

- all data needs to be sent, cue `Sendable`[#20250916actor][]

[#20250916actor]: Matthew Massicotte: "When should you use an actor?", 2025-09-06, <https://www.massicotte.org/actors>

Refactor: Extract Zettel

From the original note, a new idea presented itself and can be encapsulated. This is just like programming – you expand an algorithm, a sequence of actions, a data type, and then you notice that parts of it actually go well together under a new umbrella to encapsulate and form a new idea, a new concept.

This process is best shown in pictures, so here you go.

Select the part that should become its own thing.

In my app, The Archive, run the “Extract Zettel” plug-in function to perform the refactoring. I bind it to Cmd+Shift+X (shifted ‘Cut’).

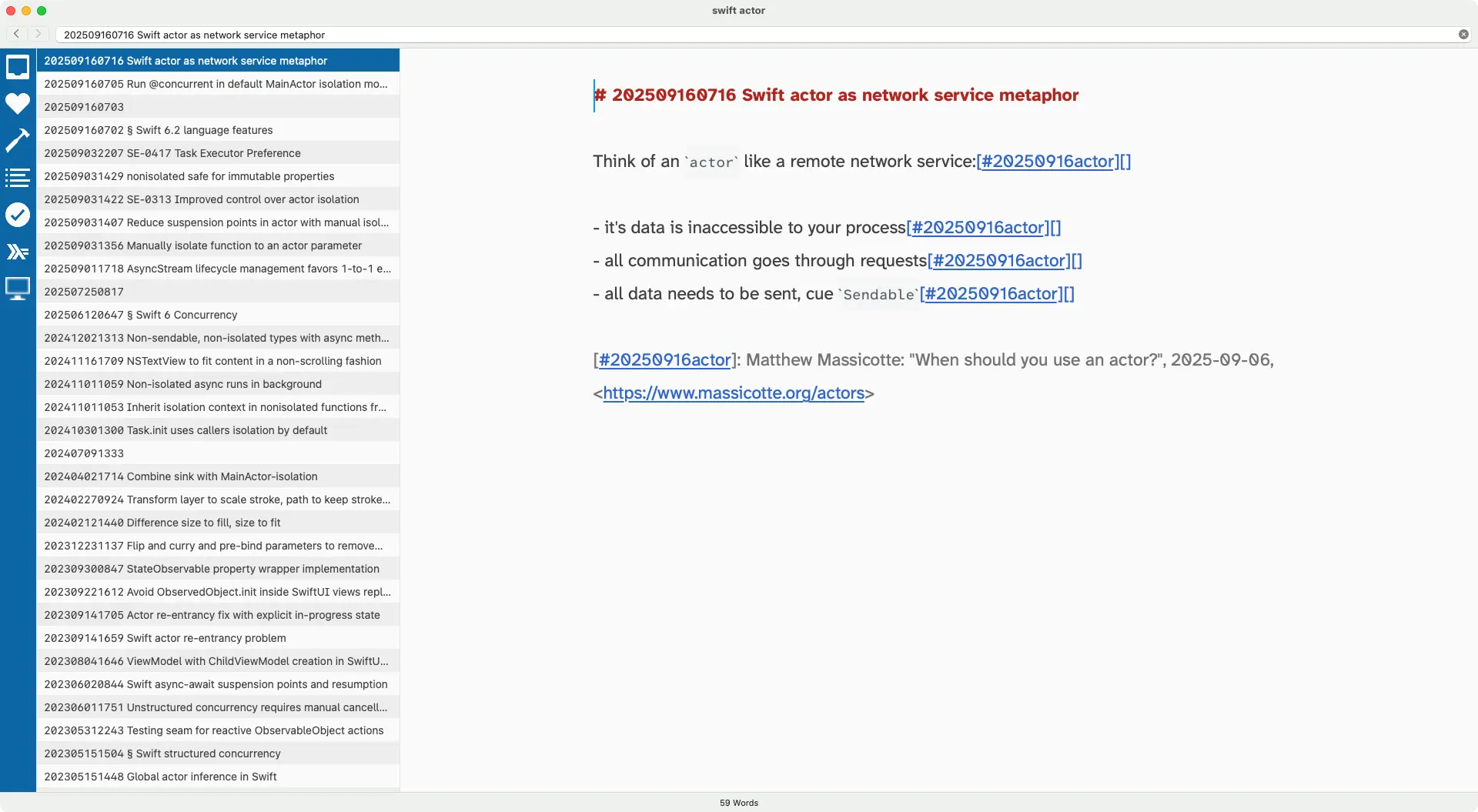

The title of that new note: “Swift actor as network service metaphor”

Confirm, and you end up with a forward link to the new note where the text used to be, and a new note with the extracted content plus a heading.

I add tags to the new note, and this is the result:

# 202509160716 Swift actor as network service metaphor

#swift #actor-isolation

Think of an `actor` like a remote network service:[#20250916actor][]

- it's data is inaccessible to your process[#20250916actor][]

- all communication goes through requests[#20250916actor][]

- all data needs to be sent, cue `Sendable`[#20250916actor][]

[#20250916actor]: Matthew Massicotte: "When should you use an actor?", 2025-09-06, <https://www.massicotte.org/actors>

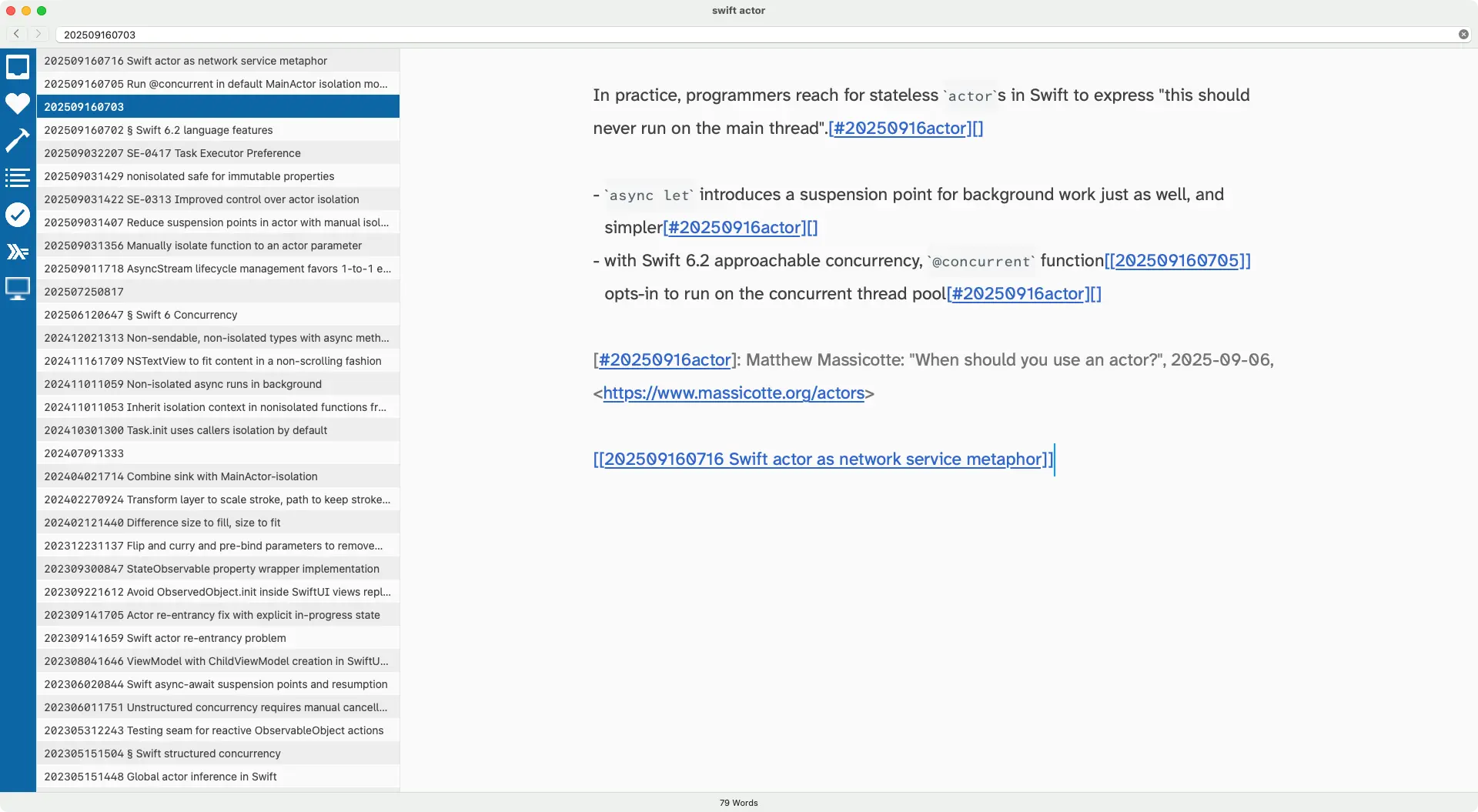

The mechanical refactoring left a line with a link that does the job, but doesn’t do it well. So I remove the line that reads

[[202509160716 Swift actor as network service metaphor]]

And insert a link at the top, integrating the metaphor into the prose:

In practice, programmers reach for stateless `actor`s in Swift to

express "this should never run on the main thread".[#20250916actor][]

That solution is overkill if you consider the overhead of using actors

like network services[[202509160716]].

...

The metaphor now acts as a one-sentence vindication that, and why, it’s overkill to use actors just to opt-out of the main actor.

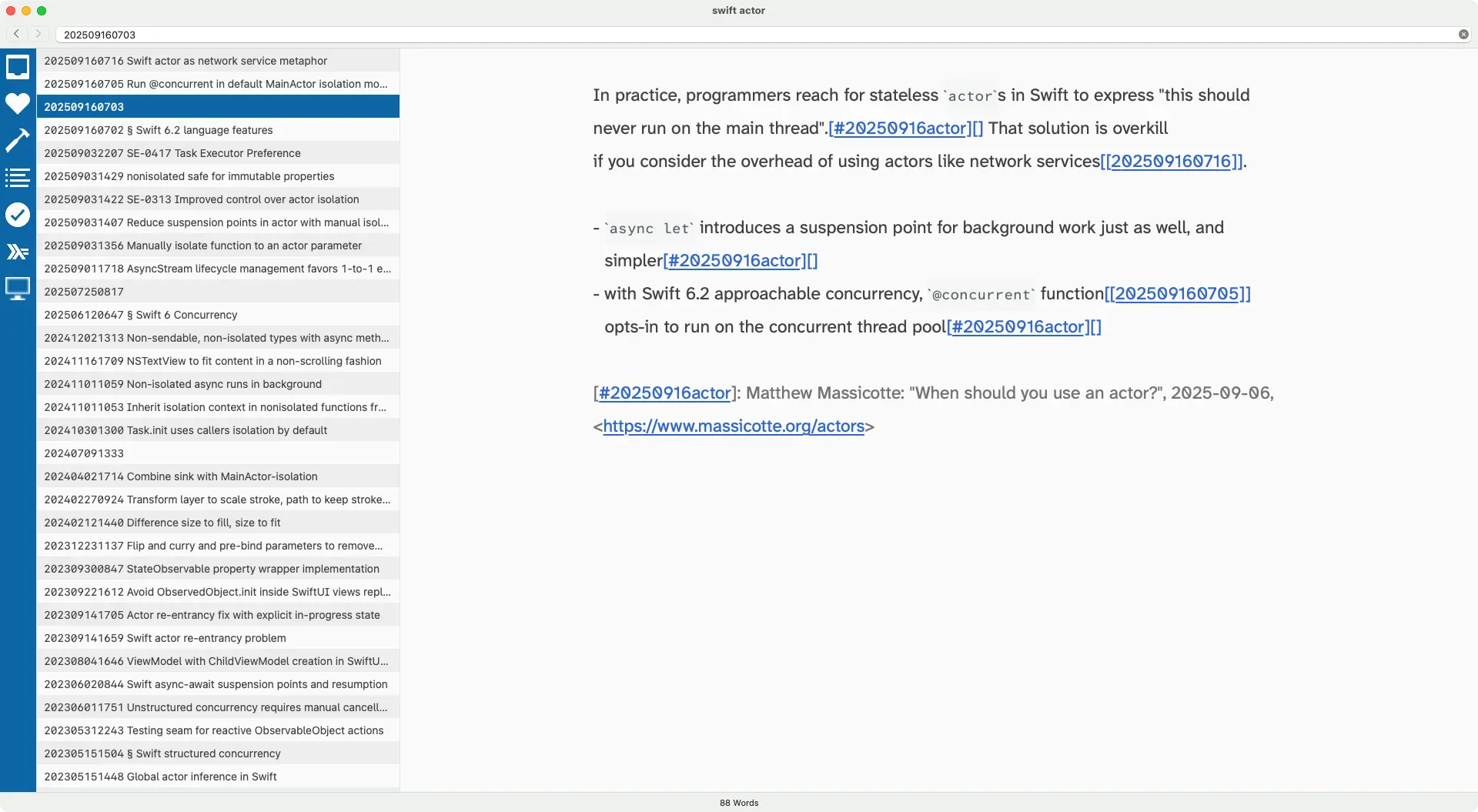

Following the link to the metaphor note to check for the flow, I now notice at a glance that two bullet points start with “all”; they are qualifiers of the first bullet. I look at Matt’s post again and notice another detail, so I change the note a bit and at the point of me writing this, the final content is:

# 202509160716 Swift actor as network service metaphor

#swift #actor-isolation

Think of an `actor` like a remote network service:[#20250916actor][]

- it's data is inaccessible to your process[#20250916actor][]

- all communication goes through requests[#20250916actor][]

- all data needs to be sent, cue `Sendable`[#20250916actor][]

- callers can't know about other processes accessing the resource at the same time[#20250916actor][]

[#20250916actor]: Matthew Massicotte: "When should you use an actor?", 2025-09-06, <https://www.massicotte.org/actors>

I like this structure better. Instead of a handful of items, there’s now a hierarchy of information.

Onward: Necessary Conditions for actor Usage

The “Questions” section in Matt’s post actually has answers:

You choose a class because you have more than one thing that requires a reference to its state. Simple.

Succinct, and primes me to expect an analogous heuristic for actors. Well done! That makes this hit harder:

Deciding on an actor is less simple. In fact, I think there are three conditions that must be satisfied to truly require an actor. First, you have some non-Sendable state. Second, operations that involve that state must be atomic. And third, those operations cannot be run on an existing actor.

While Matt himself “thinkgs there are three conditions that must be satisfied”, I’m fine with expressing this as three necessary (but maybe not sufficient) conditions. We don’t know about sufficiency – Matt doesn’t say. But it works well enough, so I paraphrase and reformat and add this to the bottom of the note again to be extracted:

Necessary conditions to introduce an actor according to Matt Massicotte:[#20250916actor][]

1. You have non-`Sendable` state.

2. Operations that involve that state must be atomic.

3. Those operations cannot be run on an existing actor.

Note that I now only place 1 citation marker, not one per condition. That is because these three conditions work as a triple. Even if Matt revises these and ends up with, say, five conditions in a year or two, that’ll be its own thing. The second revision. I would be adding it above this list, because it’ll be more recent, and probably more accurate (otherwise why would careful thinker Matt revise the list?), but the old, outdated conditions are unfazed.

The other, non-enumerated list from the start, is just a loose collection, and I expect it to grow and change over time.

Now the same dance: Extract note, rephrase the link.

The extracted note:

# 202509160821 Necessary conditions for Swift actor usage

#actor #swift-concurrency

Necessary conditions to introduce an `actor` according to Matt Massicotte:[#20250916actor][]

1. You have non-`Sendable` state.

2. Operations that involve that state must be atomic.

3. Those operations cannot be run on an existing actor.

[#20250916actor]: Matthew Massicotte: "When should you use an actor?", 2025-09-06, <https://www.massicotte.org/actors>

Massaging these conditions into the original note is more work. “Hey btw look at these conditions if you’re interested in actors” isn’t enough. A mere link does not suffice – these conditions change the overall story and approach.

Where I started with a loose collection of stuff, there’s now a new tool to make strong arguments. So let’s do that. Here is my take:

In practice, programmers reach for stateless `actor`s in Swift to

express "this should never run on the main thread".[#20250916actor][]

That isn't good reasoning, because:

- In practice ("runtime"), consider the overhead of using actors like

network services[[202509160716]].

- In principle, it doesn't satisfy any of the 3 necessary conditions

for actor usage[[202509160821]]

For that purpose, there are better tools:

- `async let` introduces a suspension point for background work just

as well, and is simpler[#20250916actor][]

- with Swift 6.2 approachable concurrency, `@concurrent`

function[[202509160705]] opts-in to run on the concurrent thread

pool[#20250916actor][]

[#20250916actor]: Matthew Massicotte: "When should you use an actor?", 2025-09-06, <https://www.massicotte.org/actors>

We still start with the same premise: why do programmers reach for actors? To get off the main thread, and state that clearly.

Now there are pragmatic reasons to not do that: there’s overhead. The metaphor illustrates this.

There are also reasons rooted in principle: none of the strong guarantees and thus upsides of an actor that offset the overhead are met if all you want is to get off the main thread. That ties things together beautifully.

Instead, use simpler tools to express “I don’t want this on the main thread/actor”.

Adding More Details to the Story

The article’s section “Why not MainActor?” ties everything together with the example of actual network client code prematurely using its own actor isolation domain. One weird sign is that all state is Sendable – that’s a code-smell, and the inversion of necessary condition number one: “you have non-Sendable state”.

Thinking about this, would the inversion of the other necessary conditions form easily detectable code smells? I start a new note and work backwards this time to explore this. However, I couldn’t come up with other easily detectable code smells for the other conditions, except “those operations cannot be run on an existing actor” inspired me to extrapolate what I read in Matt’s article:

# 202509160833 Premature actor usage code smells

#actor #swift-concurrency #code-smell

Code smells that show Swift `actor` is being used prematurely:

- The `actor`'s state is `Sendable`.[[202509160821]]

- There's only one function doing actual work -- that could just as

well be owned by a MainActor-isolated object with opt-in

`@concurrent` annotation to use the global thread

pool[[202509160705]]

The second bullet will likely evolve. It itself has the smell of an idea not fleshed out or thought through. The exaggeration of “there’s only one function” works as a code smell. For now, this is good enough for me.

No other idea presents itself immediately, so I let this rest.

I add a link to this note to the original one. Could’ve just as well started from there and Extract Note again, but I didn’t.

...

To detect potentially premature `actor` usage, see the list of code

smells:[[202509160833]]

For the purpose of getting off the main actor isolation, there are

better tools:

...

I lead with the code smell detection to make sure I don’t overlook this. A list of solutions at the end is captivating enough, and once attention is captured, and solutions to not-yet-identified problems are evaluated by the reader (i.e., future me), references like this will easily be overlooked.

That’s why I put it there; “above the fold”, essentially.

With this addition, I now notice that I want to link from the list of code smells (which is a mere collection) to the original note, the one I’m editing the whole time, because it offers reason where code smells just “exist”.

So from the code smell list, I link to the yet-unnamed original note. It has no title, but I know how I want to reference it from the perspective of future-me reading the code smell list:

Getting off the main thread is not a sufficient reason, and there are better ways to implement that requirement.[[202509160703]]

This usage of the unnamed note will likely affect what I am going to call it. This usage, the link, creates a rather strong ‘pull’.

Processing the Rest

I feel like this quote from the “Why not MainActor?” section contains a lot of insights, but I can’t quite unpack it, yet:

It can execute more than one request simultaneously, but it cannot do any other synchronous work concurrently, such as decoding responses.

How’s decoding responses ‘synchronous work’, but done ‘concurrently’? Can’t we async let escape from the actor isolation to decode before we return the decoded result, maybe? I need to verify that. That’s work and gets in the way of finishing this before I run out of time, so I leave it and ask Matt instead :)

The next section, “Actor justification”, reiterates the necessary conditions; no change or addition there. It also contains a nice quote that I append to the “202509160821 Necessary conditions for Swift actor usage” note, right after the three conditions themselves:

Explicate the requirements in doc comments:

> Every custom Swift `actor` needs justification in a comment doc that

> says “this is an actor because…” and the answer isn’t allowed to be

> “it helps deal with concurrency errors”.[#20250916actor][]

It puts the burden of explaining why an actor is used in the first place to the programmer implementing it, not people who come later and need to deal with it. That’s great practice and gels well with this note being all about “do I need an actor?” – because if you can’t explain it, maybe you don’t.

Then, in closing, “Footnote: Sendable Protocols” messes up my existing structure with a new, non-necessary, but sufficient condition! I love it. The new note:

# 202509160902 Sendable protocol conformance sufficient condition for Swift actor usage

#actor #sendable #protocol

Sendable protocols mark the whole conforming type as needing to be sendable.

Value types with sendable content can conform to this easily; but

reference types with mutable state can't. You need to use `actor`s for

that for safe concurrent access.

When writing the actor implementation, check that necessary conditions

for actor usage are met,[[202509160821]] and consider changing the API

(if it's yours) or propose changes (if it's open source) to not make

the whole protocol `Sendable` just to make the API implementation

easier.

I’m linking to the list of necessary conditions from here, and I’m linking back from there with a new paragraph at the end. This is approaching the Two Sides of a Coin Zettelkasten Pattern:

...

Needing to conform to `Sendable` protocols from other packages is not a necessary, but sufficient condition.[[202509160902]] The reason for this protocol's existence may be wrong, though, so try to change the requirement if you can.

I really want to stress that this can be a bad idea if you’re the one writing the protocol definition. So I add it to the code smells, too, with a twist:

- You made a protocol `Sendable` and now need actors, just because that makes usage simpler.[[202509160902]]

Conclusions

Writing about this took forever. A process that would’ve taken half an hour took two hours. The note ID’s show that.

Writing about my reasoning, taking pictures, rewriting, double-checking for consistency – that all increased the depth of my processing the article, but also the time it took to finish everything.

Had I not started to blog about this, I likely would’ve ended up with slightly different notes. Probably not terribly different, but the observation of the process definitely affected it.

Oh, I still need to tell you the title of the note.

I eventually settled on a claim that using actors in this particular way, as the rest of the note explains, is a bad idea:

# 202509160703 Introducing actors to escape main thread isolation misuse

#actor #isolation #heuristic

To see all notes in their final form, check out this GitHub Gist. It contains all files as of the time I finish this post.