Swipe Transitions and ReSwift

In a client meeting yesterday we tried to figure out how to animate scene transitions with swiping left/right when ReSwift is the single source of truth of the app state. What goes into the app state? How do you animate that? Should the % of the transition be part of the app state for some reason? (Spoiler: Nope.)

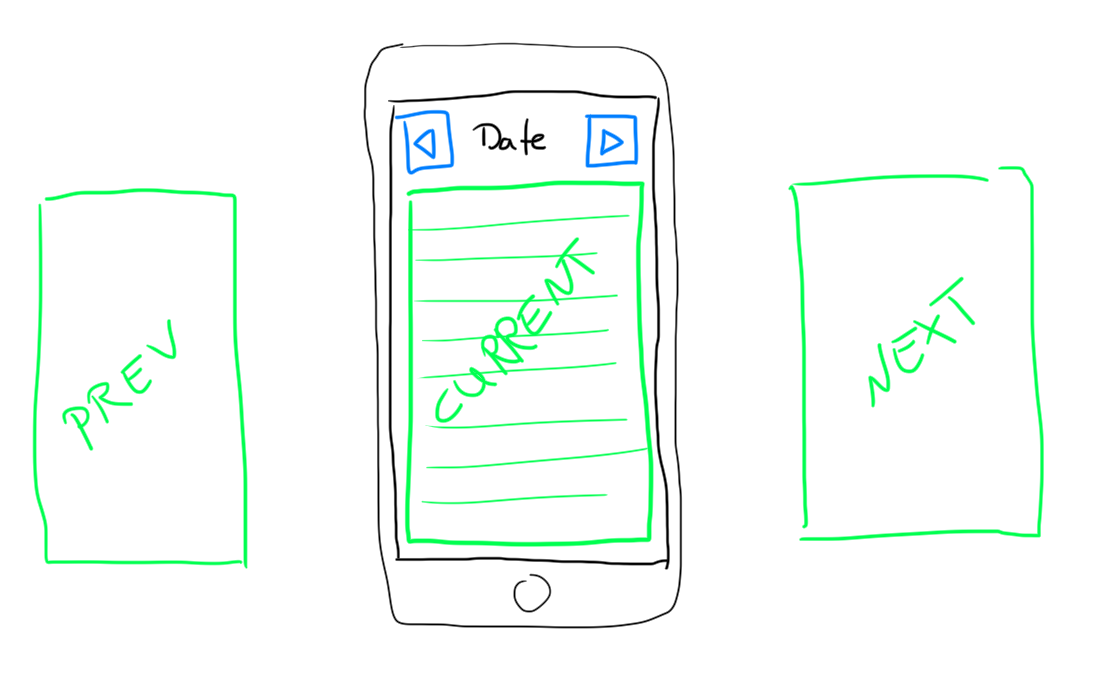

Swiping is challenging at first because this interactive transition from view controller A to B requires both to be ready for display: when you swipe, B needs to be “dragged in” visually. When you add custom navigation controls, you end up with a master view controller that contains a child view controller to display the actual table view (green box in the sketch below). These table views should be swiped in from left or right and trigger navigation changes.

In this example, the user sees data for a given day. She should navigate freely to the previous and next day with swiping and navigation buttons until the very beginning or end of time. (Or the limits of our data, whichever comes first.)

Let’s analyze implementing this.

Single-State Replacement, No Transitions

In a static world without transitions, only the “previous” and “next” buttons of the navigation bar (depicted in blue) trigger navigation changes: you tap the button, new data from the server is requested, maybe you show a loading indicator, then you replace the UITableDataSource’s contents.

Now if you use ReSwift, the currently visible collection of data is part of your app state. Keeping it simple, the table view’s cells will display text. The state looks like this:

struct AppState: ReSwift.StateType {

var contents: [String]

}

Imagine you have actions, reducers, and whatnot in place to react to navigation changes. (This may be a challenge on its own and is a topic for another day. Hint: you are going to need a “change day” action to trigger the network request and a “replace data” action to update the contents.)

To show the latest state changes, you set up a Presenter that is a ReSwift.StoreSubscriber. The newState callback is invoked when you received data from the server and replace AppState.contents. Then this array of strings is passed to the user interface for displaying. Let’s call that method updateView(linesOfText:).

Here’s an architectural side-note: the updateView(linesOfText:) method I imagine the presenter to call should be exposed by the master view controller. This in turn can delegate down to its current child view controller that handles actual display of the table. But coupling the presenter, a service object outside your presentation layer (!), to a sub-view controller may harm you in the long run. The master view controller is the outer shell of the whole component, so it’s responsible for exposing a usable interface. The amount of internal components and delegation to them is an implementation detail other objects should not care about. (You’ll see why in a second.)

This setup is pretty simple. AppState changes flow through the Presenter which creates a view model if necessary, then passes that to its view component. As a result, the UITableView is reloaded with new data and you’re done.

That’s the most barebones approach. Before you add interactive transitions, let’s make it more responsive first. Right now, each button tap triggers a network request that puts the user’s interaction to a halt. Stop-and-go navigation isn’t very popular with the kids, so we’ll pre-fetch neighboring day’s data in the next step.

Pre-Fetching Adjacent Days’ Data

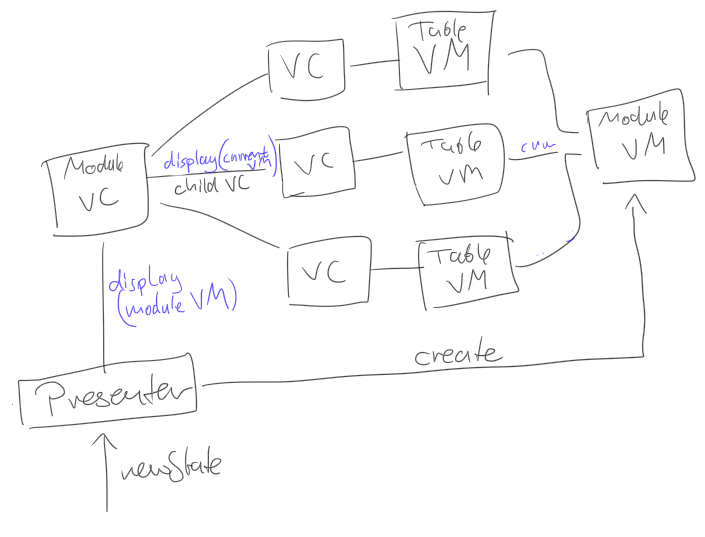

In the presentation layer, I imagine the situation to change a bit and look like this:

The changes to the simple approach from above are:

- The master view controller has 3 child view controllers instead of 1. All of them are prepared and ready for being displayed.

- Tapping a button now does 2 things: it fires a “change day” navigation action as it did before, and it immediately puts the correct child view controller on top.

- To make all this possible, the

Presenterassembles aViewModelwith 3 content arrays instead of 1.

The view model is still pretty simple:

struct ViewModel {

let previousDayData: [String]

let currentDayData: [String]

let nextDayData: [String]

}

The master view controller accepts this in the new updateView(viewModel: ViewModel) method.

class MasterViewController: UIViewController, View {

let previousDayViewController: ChildViewController

let currentDayViewController: ChildViewController

let nextDayViewController: ChildViewController

// ... setup of the child view controllers etc. ...

func updateView(viewModel: ViewModel) {

// Assign each data array to its child view controller

prepareChildViewControllers(viewModel: viewModel)

// Put "current day" on top, hide the others

resetTopmostViewController()

}

}

The app state has to reflect this overall change, too, so the Presenter can assemble a view model in the first place. I call this triple a “deck” of model data. In this contrived example, the model data is just as simple as the view model. Usually, real model data is more complex and uses custom types a lot more, and in the view model you resort to easy-to-display types. So although here both ViewModel and Deck are equally simple, I want to stress the point of giving your model types names that make sense, and not just re-use the ViewModel type from your outermost UI layer in your app’s very core.

struct Deck {

let previous: [String]

let current: [String]

let next: [String]

}

struct AppState: ReSwift.StateType {

var deck: Deck

}

And finally, the presenter which assembles all:

protocol View {

func updateView(viewModel: ViewModel)

}

class Presenter: ReSwift.StoreSubscriber {

let view: View

func newState(_ state: Deck) {

let viewModel = ViewModel(

previousDayData: state.previous,

currentDayData: state.current

nextDayData: state.next)

view.updateView(viewModel: viewModel)

}

}

The effects of this change: “previous”/”next” content changes happen instantly, and while a request can take a couple of seconds, the user can already interact with the pre-fetched set of data.

Initially, resetting and replacing the currently visible child view controller and its contents will not feel right.

What’s going to happen:

- the user taps “previous”

- another table view with new data is displayed immediately, how delightful!

- the user scrolls down a bit

- (meanwhile, the request finished and the state update is triggered right now)

- the view flickers and is reset, the table scrolled to top, displaying the same data as before; huh?!

Offering immediate transitions in the view layer and then resetting it hard from the core of the app causes problems for the user interaction. It takes a bit of an effort to make this smooth. In a nutshell, here’s what I’d do:

- Use an array differ like Dwifft to compute the changes of the incoming

viewModel.currentDayDatawith the stuff that’s on screen; if the data isn’t stale, no need to reload the table view. If it is stale, Dwifft will offer delta updates, which means you get animated insertion and removal table changes instead of a full reset. - When

updateViewis invoked, switch child view controller references. Before this change,previousDayViewControllerbecame visible. But there was no “previous-to-that” view controller. Resetting which one is on top now can become “exchangepreviousDayViewControllerwithcurrentDayViewController” and then perform the content diffing. That’s probably easier than transferring control of the visible table tocurrentDayViewControlleror similar. And you will need to makecurrentDayViewControllerpoint to the topmost child view controller in order to make the navigation buttons work again.

Adding Swipe Gestures

I’m no expert in interactive view controller transitions. So my advice for this part is really sketchy:

- Only your view layer is responsible to handle the swipe transition. It should not leak into your app’s state or something. It’s just a special kind of animation.

- During the transition, nothing really happens, except the screen contents animate.

- When the gesture and transition have completed, say “swipe from left to right” to pull in the previous day’s data, only then trigger a state update.

- The completion of a swipe transition is 100% similar to tapping the “previous” or “next” buttons.

With the setup from the previous step, this should already be everything you need to do.

Because users expect to swipe on for a while without interruption, you may want to increase the range of your Deck and ViewModel in both directions: instead of pre-fetching 1 set of data, you may want to pre-fetch 3 or more. Or you pre-fetch 2 in both directions (2 + 1 + 2 = 5 in total) by default and change that to 4 in the direction the user is swiping (2 + 1 + 4 = 7 in total).

In the end, you’ll want to make sure that no matter how much you are pre-fetching, the request–response cycle shouldn’t take too long or the interaction will come to a halt again. In another iteration, you can refine the process and dispatch more granular state updates: first, request the new “current” day’s state and make sure the data hits your AppState quickly, then fire off another request for the immediate neighbors; then another one for farther away screens.

Conclusion

It turned out that “swiping between screens” boils down to:

- Screen transitions: switch between views of pre-fetched sets of data for high responsiveness.

- Adjust the app state to represent what your app needs, not the domain model; if you need to pre-fetch data, store the datasets as part of the state.

- Interactive and animated transitions are solely part of the UI layer’s responsibility and don’t affect state.

I want to postulate this: whenever you see the term “animation”, it’s just a presentation detail. It should be exclusively managed by the UI layer. If your domain model (the innermost core) knows about animation progress, you screwed up somewhere along the way. Similarly, the app state (the mediation layer between model and UI, if you will) should not know about animations, only discrete state changes.

Now prove me wrong!