Solve database mapping problems and the impedance problem of ActiveRecord

Some time ago, I read about database design and mapping object hierarchies to database tables. Ruby on Rails’ default approach is to use a technique called Single-Table Inheritance. This design pattern has some drawbacks.

In short, the domain model design should come first, proper database design second, and only last comes the decision how you persist your objects. Ruby on Rails, while not prohibiting this approach, doesn’t really encourage you to make informed decisions about these three steps. I aim to tell you something about stage two and three so you’re design decisions might improve.

I’ve made heavy use of my Zettelkasten to compose this post. The list of Zettel I used are at the bottom of the post.

Database Normalization and the Impedance Problem

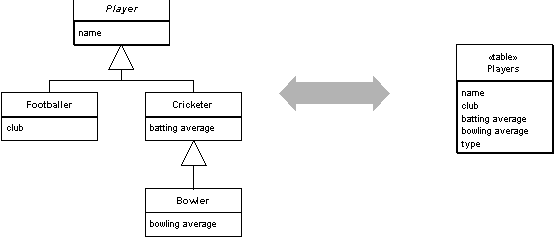

Single-Table Inheritance (STI) fills unused columns with NULL depending on the object which is persisted. Look at the image above. If you store a Footballer object into the database table Players, only the columns name and club will be used. The two others will be NULLed-out.

This ruins your database normalization. According to [Jacobson 1990], p 273, The table Players would be in third normal form …

if, and only if, for all times, each row consists of a unique object identifier together with a number of mutually independent attribute values

How could this be broken in STI?

Think about a column sum_total which stores the sum of columns price and shipping. Database tables won’t ensure that sum_total is updated once you changed price, hence you’re prone to data inconsistency. sum_total is redundant since it repeats information you already have. (See the book by Jacobson, p. 273, too.)

Polluting the table with NULL values is adding dependency between the columns, too. It doesn’t make sense to fill in both club and bowling average for a single object or table row, although that combination is totally possible in your table. Your code probably won’t assign both attributes at once, one belonging to a Footballer, the other to a Bowler entity, but your database cannot be trained to adhere to the same principles. STI introduces bad database design for the sake of coder’s convenience.

The Ruby on Rails mentality to “let the database be dumb and the app be smart” isn’t to be depended on: Nathan Long pointed out he switched frameworks and languages over the years but had to keep the database. That’s a good reason to worry about database design and sustainable data integrity first and consider shortcuts your current programming framework provides second.

Object-oriented programming encourages objects with complex attributes. Objects have both primitive values and connections to other objects, the latter called “complex”. Relational Database Management Systems (RDBMS) like MySQL are only capable of storing primitive data types like integers and text, though. Object’s mutual attribute exclusivity can’t be expressed in RDBMS, either.

This incompatibility is called the impedance problem. (See pp. 269–283, notably p. 271, in [Jacobson 1990].) You’d need to map complex attributes like object references to other tables. A way out is to use Object Database Management Systems (ODBMS) to store objects and their relationships directly. Another way is to improve your database design drastically, which I suggest you do.

Solving the Impedance Problem with Good Design

Your database design will need to differ from your domain model because class hierarchies cannot be expressed in databases easily and you wouldn’t want to get the easy pie by throwing database integrity away, buying into redundancy.

Consider the image above. The same class hierarchy as before is shown, but the database design is fundamentally different: specifications of Player like Bowler get their own details table. When you fetch a Bowler object from the database, you’d have to query both the Players and Bowlers table to get all the data.

This technique or design pattern is called Class-Table Inheritance (“CTI”, see [Fowler 2009]). It solves the impedance problem in a sane way, utilizing two-dimensional mapping. (See p. 275f in [Jacobson 1990].)

I’d call creating an Entity–Attribute–Value Model (EAV) an insane solution. EAV maps all attributes to relationships. Your object’s table would consist of these columns:

- Entity,

- Attribute, a “Foreign Key” reference to the attribute’s definition, and

- the Value of the Attribute.

To me, this is a few miles too far from the domain model. I wouldn’t know how a database schema could be any more distanced from the objects it persists.

If you want to see some CTI applications, the Ruby gem Sequel has an adapter for that. There’s a post by Pablo Astigarraga with good example code using the Sequel gem. Nathan Long on the other hand posted a minimal solution on top of Rails’ ActiveRecord.

Mix all the Things into Repositories

It occured to me that you wouldn’t need to persist every object in the same way. If your design doesn’t suck, your domain model is independent from persistency mechanisms like ActiveRecord. Making use of a Repository object which hides the database from the domain and translates search criteria to database queries helps. (For the patterns, see [Fowler 2009].)

Some entities can be accessed and stored behind the curtains via Rails’ ActiveRecord. Others can be modeled according to the Class-Table Inheritance pattern.

The entities’ repositories will be able to chose which persistency mechanism they utilize. You can implement this nicely as a Strategy which can be plugged into the Repositories.

Bonus: you can stub the repository strategy during tests. I took the example from Eric Evans’ Domain-Driven Design ( [Evans 2006]), and wrote a Gist in Ruby.

Discussion

Ruby on Rails is all about convenience. I was all in for that for a very long time. Every book on software architecture I read tought me to do things different, tough. I now consider Rails’ ActiveRecord class an anti-pattern: it mixes the responsibilities of persistency, data validation and more into one single fat model object. It can work without problem in lots of cases. But it can also cause trouble in others.

For example, ActiveRecord rewards you with a single point of data validation. These objects not only check for proper data types (fail when user tries to assign a String to an Integer attribute) and object consistency. They also check for database table coherence: is the user name unique or has someone already taken it?

The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) suggests you validate objects on three layers in your web applications:

- Persistency/Database: validate against SQL injections, for example

- Presentation/Views: validate boundaries like character counts

- Domain Model: validate attribute consistency, ensure business rules are met

That’s a lot more work on your side if you don’t mix everything into one object!

It raises the likelihood of making future changes painless, though. This seemingly complex three-layered design (compared to inheriting from ActiveRecord::Base!) adheres to the Open/Closed Principle, which says “a module should be open for extension but closed for modification, see [Martin 2000]. You can exchange parts and, for as long as the parts implement a common interface, expect the system to continue running smoothly.

Your code benefits from the Repository-Strategy combo pattern I already introduced for the same reason. We need to design software not only to be open for extension but for change, too, because along the way some things will eventually change. Good object-oriented design prepares your application for change. (Via [Metz 2013])

That’s why they call the “lock-in effect” the lock-in effect: once you’re in, the cost of switching increases significantly. Adhering to Rails’ conventional way of implementing stuff can make you vulnerable against unexpected changes in the long run.

Conclusion

There are many different ways to approach software architecture. Every angle seems to have its own pros and cons, leaving you to wonder what’s right in your case. You’ll become a better designer if you learn about the alternatives. Becoming a better designer will improve your decisions when writing software because you will be able to make informed decisions.

Ruby on Rails lowers the bar of getting a walking skeleton up and running by magnitude. It’s great for prototyping and sketching web applications. Rails is kind of open for extension, too: you can ditch the training wheels of ActiveRecord and roll your own persistency layer, for example, without inhibiting a lot of pain. I hope you learned why this might be a good decision:

- Database design comes after domain modeling but before programming persistency mechanisms. Keep in mind that your database will eventually survive the code you’re about to write.

ActiveRecordmixes responsibilities, increasing domain model pollution and locking you into it’s own way of doing things. Don’t decide on the easy path only because it’s convenient. That’s not a well-informed but a clueless way to decide.- Mapping object and class hierarchies to database tables can be hard. You can solve the impedance problem with the Class-Table Inheritance pattern. Again, Rails points to the easier solution of STI but wreaks havoc with your database design.

(The links are affiliate links to Amazon.)

[Jacobson 1990]: Ivar Jacobson, Magnus Christerson, Patrik Jonsson, and Gunnar Övergaard (1990): Object-Oriented Software Engineering. A Use Case Driven Approach, Wokingham: Addison-Wesley.[Fowler 2009]: Martin Fowler (2009): Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, Boston: Addison-Wesley.[Evans 2006]: Eric Evans (2006): Domain-Driven Design. Tackling complexity in the heart of software, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley.[Martin 2000]: Robert C. Martin (2000): Design Principles and Design Patterns, 2000. Download PDF[Metz 2013]: Sandi Metz (2013): Practical object-oriented design in Ruby: an agile primer, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley.

I pulled the following Zettel to assemble this post:

201307291910 Persistency mechanisms can vary per entity201305161728 Validate multiple layers201305101927 STI denormalizes database tables201305101924 Database normalization201305101917 Impedance Problem201305091507 Class-Table Inheritance instead of STI201305031836 Open--Closed Principle201305012044 Entity--Attribute--Value Model