Zettelkasten for Programmers: Documenting Confusing with Swift.SendableMetatype

I was reading the SendableMetatype docs because the new NotificationCenter messages I was catching up on use that in the API headers.

I was reading the SendableMetatype docs because the new NotificationCenter messages I was catching up on use that in the API headers.

I learned threee new things when I read Doug Gregor’s “Improving the usability of C libraries in Swift” blog post that may also affect your daily life importing C libraries:

.h files;SWIFT_NAME annotation can be used to make free C functions act like methods on objects;Until today, I was under the impression that you can make C functions sound a little bit nicer and add argument labels with SWIFT_NAME mostly, but this is something on a different level.

One Example to turn a free function into a method:[#20260123webgpu][]

WGPU_EXPORT void wgpuQueueWriteBuffer(

WGPUQueue queue, WGPUBuffer buffer, uint64_t bufferOffset, void const * data, size_t size)

WGPU_FUNCTION_ATTRIBUTE SWIFT_NAME("WGPUQueueImpl.writeBuffer(self:buffer:bufferOffset:data:size:)");

That’s what got me interested: object-oriented conventions from C, expressed in Swift’s notation! Where does the type come from? Usually, you just get opaque pointers.

The WGPUQueueImpl typealias is generated as well with a different annotation – that’s now becoming a reference-counting wrapper around WGPUQueue instead of an opaque pointer. The heavy lifting of this is done by a parameterized annotation, SWIFT_SHARED_REFERENCE(increment, decrement), to which you pass function names to increment and decrement the refcount.

The annotation, if you would apply it manually in the header, would look like this:

// Original typedef is:

// typedef struct WGPUQueueImpl* WGPUQueue WGPU_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTE;

typedef struct

SWIFT_SHARED_REFERENCE(wgpuGroupAddRef, wgpuGroupRelease)

WGPUQueueImpl* WGPUQueue WGPU_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTE;

… making the generated Swift interface:

// Original generated typealias would've been:

// public typealias WGPUGroup = OpaquePointer

public class WGPUGroupImpl { }

public typealias WGPUGroup = WGPUGroupImpl

Now the secret ingredient to make this bearable is to not copy the header files, but to use a YAML “sidecar” file to instruct clang to generate a different API. Combining the generated type declaration and the method example from above:

- Name: WGPUGroupImpl

SwiftImportAs: reference

SwiftReleaseOp: wgpuGroupRelease

SwiftRetainOp: wgpuGroupAddRef

- Name: wgpuQueueWriteBuffer

SwiftName: WGPUQueueImpl.writeBuffer(self:buffer:bufferOffset:data:size:)

clang supports API notes in a YAML file to annotate .h files without having to change the .h files themselves for module imports. That’s so neat: with that you can wrap C libraries in Swift without having to maintain a copy of the headers.

Clang will search for API notes files next to module maps only when passed the

-fapinotes-modulesoption.

Next to methods, properties also work with SWIFT_NAME annotations:

- Name: wgpuQuerySetGetCount

SwiftName: getter:WGPUQuerySetImpl.count(self:)

- Name: wgpuQuerySetGetType

SwiftName: getter:WGPUQuerySetImpl.type(self:)

Depending on the C API, this can be a game-changer in terms of Swift language ergonomics for you and your team. No more manual refcounting (which, if limited to e.g. a function scope, isn’t that bad thanks to defer, but can get hairy when you need to escape and keep references alive for longer), proper Swift types instead of opaque pointers, and methods and properties on these types instead of namespaced free functions. Lovely.

God was this weird to figure out. So swift test will produce a lot of stuff on standard output. Test failures, to nobody’s help, also just list the file names, not the (relative) paths: In theory, MyTest.swift:12:34 is enough to instruct an editor where to look for the test failure.

I’ve been browsing the Swift Forums for something the other day that was related to sendability of NSItemProvider. I found this reply by Holly Borla – the question doesn’t matter much, I promise: Holly Borla (2024-10-14):

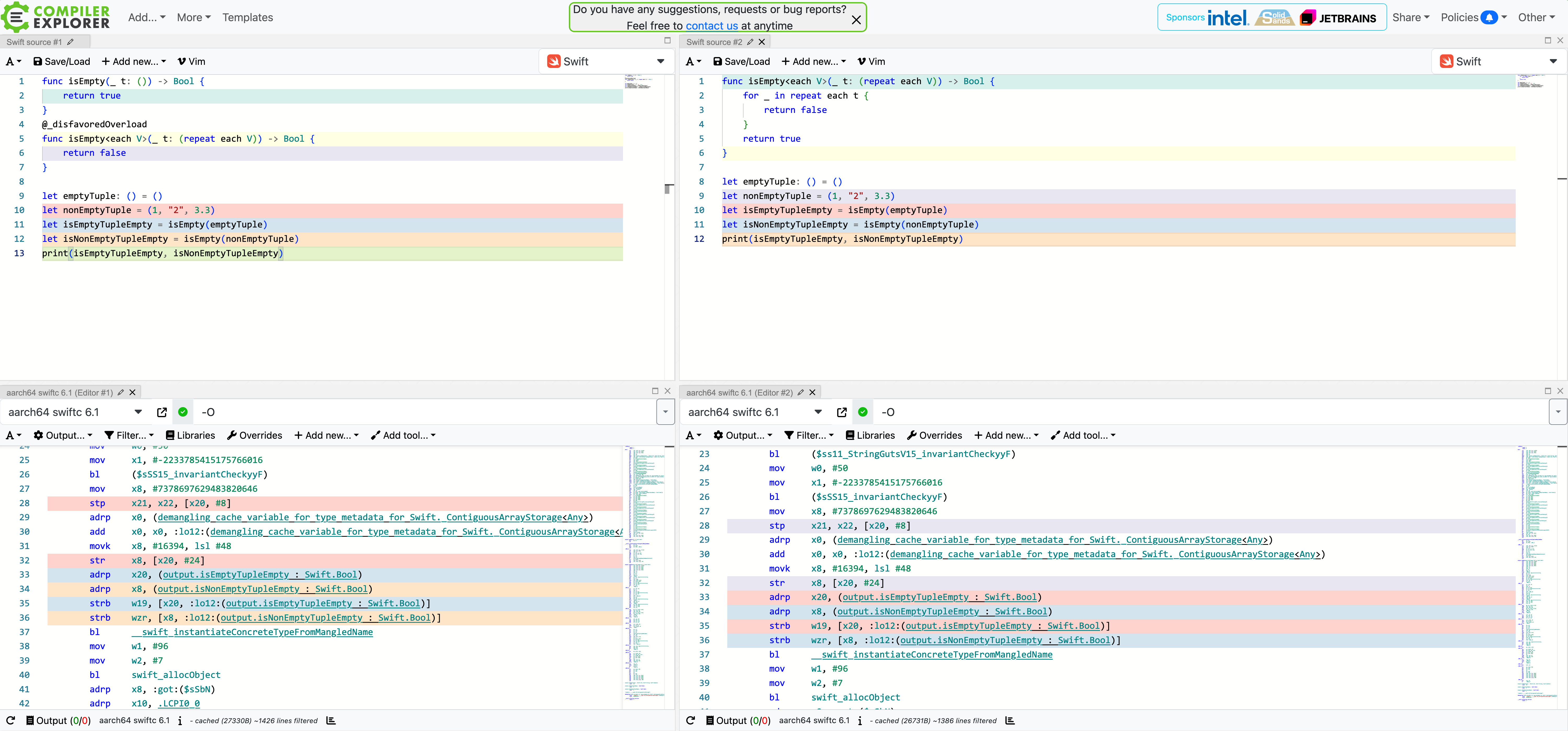

Rick van Voorden in yesterday’s Open Office hour told me about the fact that variadic types in Swift can, in fact, have an empty list of associated types. A quick refresher of variadic types in Swift using parameter packs:

Not all Swift code can directly be made available to C – or rather via C to other ecosystems that allow FFI (foreign function interfaces) from C libraries. The key is twofold: The following is based on this Gist by Julian Kirsch : https://gist.github.com/HiImJulien/c79f07a8a619431b88ea33cca51de787

So I was happy spending a couple of days working on a Markdown pipeline. One that would allow me to process Markdown files, perform automated tasks, then produce 2 results: The swift-markdown package wraps the cmark CommonMark parser and offers a really nice to use API. Also Marin told me on every other occasion that I should try it, it’s good :)

Helge Heß pointed out that naive usage of Pipe in child Processes can break your program if you pipe too much data. I wasn’t aware of this, followed his references, and here are my findings. Older Mac OS X versions had a pipe buffer size of 16KiB by default, offering 64KiB on demand; in my N=1 test on an M1 with macOS 14, I always get 64KiB buffers, even if I only send 1 Byte. Run pipe buffer size discovery tests yourself to check.

Type-Driven Design with Swift by Alex Ozun from this year’s SwiftCraft is a recommended watch.

Alex covers concepts like replacing the notion of validation user input (with true/false results to represent its validity) with the notion of parsing – transforming unprocessed values into processed ones that uphold certain guarantees, like matching a string pattern. For example for email addresses.

The biggest idea tying all of the things Alex covers together is iteratively using Swift’s strong type system to sketch and then build a domain that ensures certain classes of mistakes are impossible to make. Because if you would try to do them, the compiler would complain.

I also put into my Zettelkasten a couple of concepts that didn’t have a home before, like

Swift is full of syntactic sugar. One particular taste of sweet is the callAsFunction feature. If a type has a method of that name, you can call an instance or value of that type like a function. That’s used in SwiftUI to pass actions around in the environment, for example. Quick demo: See how the call looks like there’s a function updateWidgets(newerThan:) but actually it’s calling the value itself?

Swift KeyPath is a great shortcut for property-based mapping and filtering of collections: When you need a simple transformation, the simplest probably being the boolean negation operator, you only have two choices: So either you use the key path and separate the negation – which makes it harder to read as “I want the opposite of X”. Or you drop the key path and use a regular closure.

I suggested the use of UserDefaults.register(defaults:) today. During the conversation, I realized that this behaves very much like the Optional/Nil-Coalescing operator ??.

The Swift standard library has a mutating func append(contentsOf:), but not an immutable variant. Usually, the Array and Collection types offer both. I wonder why that’s not the case here. To be fair, the concatenation operator + does the same trick.

Natalia Panferova writes about Swift enum pattern matching with extra conditions and goes over:

switch-case statements,switch-case statements with where clauses,for-in loops with where clauses,while loops with extra conditions (case let matching),if-case statements.catch ... where in try-catch blocks.)I believe there’s tremendous value in summaries like these to learn the Swift programming language and its syntax: these short summaries show a slice of different aspects of the language in close proximity.

The Swift language book tells you all about the structural programming features one after another in the Control Flow chapter: if, for, while, etc.

It also has a section on where, but that’s limited to the switch conditional statement.

The section on for loops doesn’t mention where clauses at all! You need to go to the Language Reference part of the book, where the formal grammar is explained, to read that a where-clause? is allowed.

for-in-statement →

forcase? patterninexpression where-clause? code-block

So a post like Natalia’s reminds us about the similarity of different aspects of the Swift programming language.

It’s zooming in on where-clauses, and so the reader gets to know a different “view” into the syntax as a whole that is different from the book’s presentation.

This should be very valuable to get from beginner-level understanding of “I can do things in Swift” to a deeper understanding of recognizing similarities across different aspects of the programming language.

These should, in my opinion, be included in the language’s handbook to help with “deep learning”. Until then, I’m glad we have posts like Natalia’s!

Helge Heß recently posted on Mastodon that he “still find[s] it disturbing how many #SwiftLang devs implement Equatable as something that breaks the Equatable contract, just to please some API requiring it. Feels like they usually should implement Identifiable and build on top of that instead.”

I may be 7 years late or so – but until last week, I didn’t realize that didSet property observers would fire when the observed property hasn’t actually changed. All you need is a mutating func that doesn’t even need to mutate. This can be illustrated with a simple piece of code:

In Swift, you can weak-ify references to self in escaping closures, and then you need to deal with the case that the reference is gone when the block is called. Last month, Benoit Pasquier and Chris Downie presented different takes on the problem. That discussion was excellent. It prompted me to take some more time to revisit this problem systematically, and I took away a couple of notes for future-me.

Today’s WTF moment with Swift is related to switch-case and the pattern matching operator, ~=. Defining operator overloads for special cases can help to keep case statements readable. And I thought it’d be simple enough to quickly check the setup, but I was in for a surprise!

I found it weird to form the union of two CharacterSet instances by calling the union method on one element: This chains nicely, but what pops out to me looking at the line of code is the CharacterSet, then something about URLs, and then I scan the line to see what kind of statement this is – some lengthy stuff that looks like chained method calls at first glance due to the length and the many dots.

You and I are probably pretty familiar with the XCTestExpectations helper expectation(description:) that we can .fulfill() in an async callback, and then wait in the test case for that to happen. When you have neither async callbacks or notifications handy from which you can create test expectations, then there’s a NSPredicate-based version, too. Like all NSPredicates, it works with key–value-coding, or with block-based checks. These run periodically to check if the predicate resolves to “true”.

I wanted to make sure that I’m up-to-date in regards to Swift’s lazy initialization of static attributes. So here’s a demonstration of a Swift property wrapper that produces debug output to check what’s going on, aka caveman debugging (because of the log statement, y’know). The output is as follows, demonstrating that the static var is initialized lazily when you access it:

When you look at the docs for String.index(_:offsetBy:limitedBy:), you get this description: Returns an index that is the specified distance from the given index, unless that distance is beyond a given limiting index.

With some luck, all my Windows programming wet dream might actually come true one day. There’s progress on making Swift available on Windows, and there’s progress on providing a Win32 API wrapper for Swift so you can share model code across platforms and write UI for Windows and Mac separately.

Check out the GitHub repo: https://github.com/compnerd/swift-win32

It’s experimental, but apparently way less experimental than it was a year ago!

When you write a Swift type, you should prefer to write its tests in Swift, too. In a mixed-language code base, you will run into the situation where your Objective-C tests need to reference Swift types to initialize and pass to the object under test. That’s a different story. But you cannot import the generated -Swift.h out-of-the-box:

I am upgrading the code base of the Word Counter to Swift 3. Yeah, you read that right. I didn’t touch the Swift code base for almost 2 years now. Horrible, I know – and I’m punished for deferring this so long in every module I try to convert and build. One very interesting problem was runtime crashes in a submodule I build where URLs were nil all of a sudden. This code from 2015 (!!) used to work:

During the time between Christmas and New Year, which we tend to call the time “between the years” where I live in Germany, I wanted to do something fun, but not too fun so I don’t get spoiled. That’s how I turned up experimenting to use libMultiMarkdown from within a Swift app. The amount of fun I have when reading and writing C code is negligible, which made it a perfect fit.

Dependency Injection means you do not create objects where you use them but “inject” objects a function/method/object depends on from outside. This is a useful trick to make code testable, for example. Once you adopt the mindset, it becomes second nature. From the Java world stems the imperative to program against interfaces, not implementations. In Swift, this means to define injected dependencies not as concrete types but as protocols.

I couldn’t find a simple answer on the web at first, so here’s my take for Googlers. When you need NSGlyph (which is a UInt32), you probably want to use NSATSTypesetter.insertGlyph(_:atGlyphIndex:characterIndex:) or NSGlyphStorage.insertGlyphs(_:length:forStartingGlyphAt:characterIndex:) which in turn is implemented by NSLayoutManager. But the useful glyph types to use like NSControlGlyph are Ints. How do you get a NSGlyph-pointer from these?

For quite a while I didn’t notice Sequence.first(where:) exists. It’s like first, only with a condition. Proposed and implemented by Russ Bishop, by the way. I have now happily migrated from my self-baked findFirst to this method – only to find out today that there’s not last(where:) equivalent.

The following code works as expected: But do you know what “expected” means in this case? As a reader, you assume the author had an intention. You look for the mens auctoris and are an overall benevolent reader, I hope. Presupposing said intention, you may assume that it does something special if you put the call to items.removeAll() in a defer block.

If you want to encapsulate the notion of “either A or B” (also called “lifting” in functional parlance), an enum type in Swift is the best fit: You can use associated values to wrap types with enums, too: These things seem to be expressible through a common ancestor type or protocol. But bananas and apples can be modeled in totally different manners (apart from sharing nutritional value, for example).

Found this nice post about using Swift protocols to expose read-only properties of Core Data managed objects so you don’t couple your whole app to Core Data. Using Swift protocols in Core Data NSManagedObjects is a great way to limit the visibility of properties and methods. In my 1st book on Mac app development I talked about this, too, and this is a lot easier to handle than a custom layer of structs that you have to map to NSManagedObject and back again. Core Data is designed to be invasive and convenient. It’s not designed to be used as a simple object-relational mapper.

I found the Foundation way to check for file existence very roundabout. It returns 1 boolean to indicate existence and you can have another boolean indicate if the item is a directory – passed by reference, like you used to in Objective-C land. That’s a silent cry for an enum. So I created a simple wrapper that tells me what to expect at a given URL:

Shopify published amazing/epic stats for their Ruby on Rails “app”:

Makes you wonder:

Swift changed the game a bit. Now it’s very convenient to create a new type. You don’t need to do the .h/.m file dance anymore but can start a new type declaration wherever you are. (Except when you’re inside a generic type.) That makes it more likely we devs stop to shy away from smaller types.

But it’s still a job for our community’s culture to unlearn coding huge classes (massive view controller syndrome, anyone?) and splitting stuff.

Ruby has a long tradition of super-focused methods and very small classes. Swift is just as terse and powerful in that regard. Now it’s your turn to experiment with writing types for very simple tasks. Like the Extract Parameter Object refactoring, where you lift things that go together into a new type.

Can be as easy as writing:

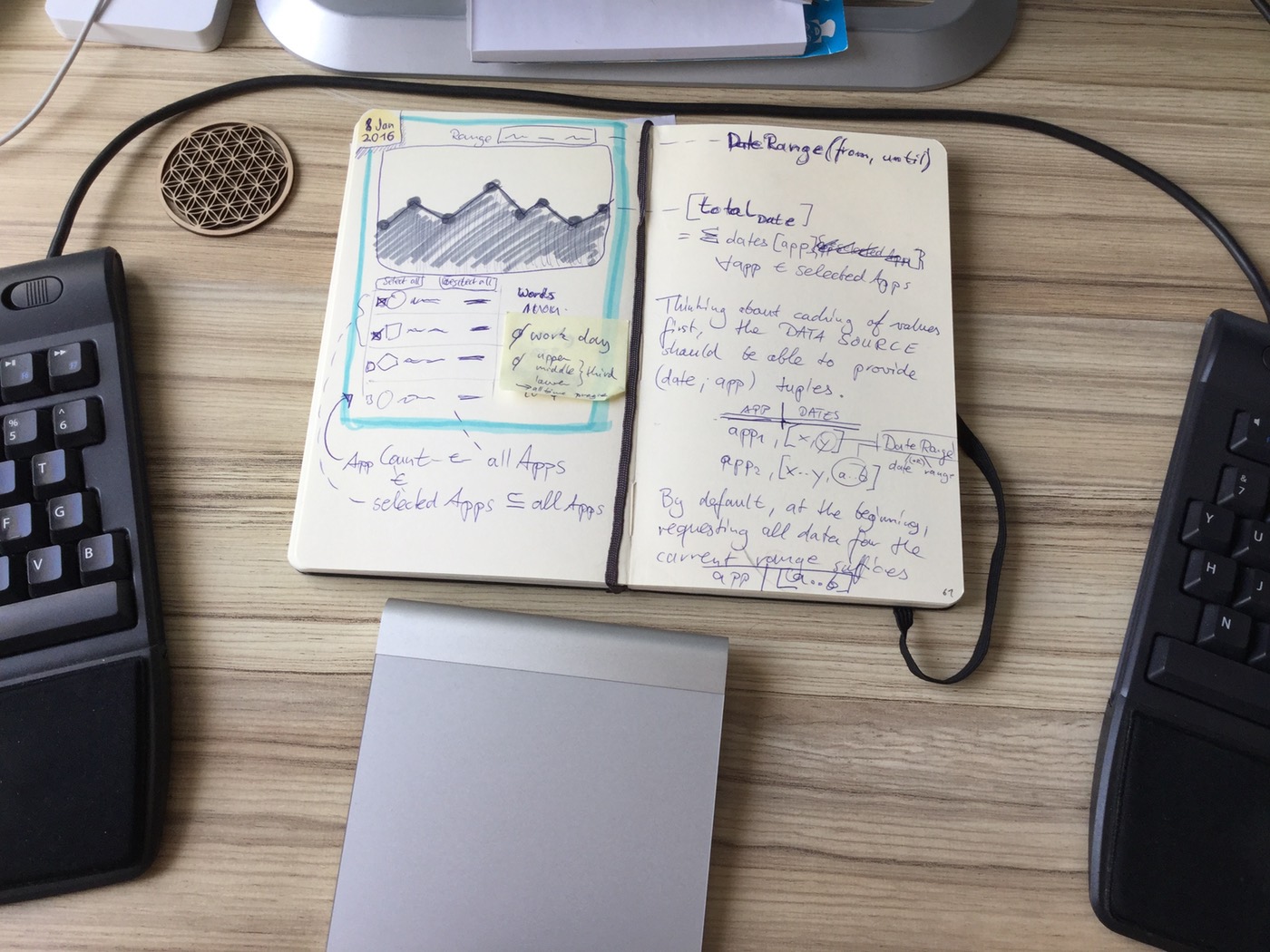

struct DateRange {

let start: Date

let end: Date

}

Et voilà, there you have a new explicit concept in your code base.

I’m converting code for my first book to Swift 3. It uses Cocoa Bindings a lot, including NSTreeController. Now the compiler changed; and one of the issues I faced was working with the NSTreeController.arrangedObjects. The compiler assumed a wrong type of the children property (see the docs) and reported “Ambiguous use of ‘children’”.

Apple have responded to my issues with broken NSLocale property availability. The properties are actually convenience accessors which you can re-impement youself for use before iOS 10. These properties are new in iOS 10, and you could add equivalent properties for older OSes using an extension like the one shown below:

We’re converting a rather big and clumsy project to Swift 2.3 at the moment. Strangely, NSLocale gives us a lot of headaches. The API hasn’t changed visibly, but the implementation seems to have. From Objective-C’s point of view: And from Swift’s: That property certainly isn’t new. Neither are the dozen others in that header file from Foundation.

Swift.assert bit me, and it bit pretty hard. What do you expect to happen in this code: … compared to this code: If your answer is “only the second variant will actually execute sendAction in release builds,” then you’re way smarter than I. Until now I assumed that Swift.assert behaves similar to assertion macros in Objective-C where the code is passed through in release builds. I never cared to read the documentation:

I ran into trouble with custom collections the other day and wondered how to reliably find out what the bare minimum for a custom CollectionType is. The compiler will only help a bit: It’s conforming to neither CollectionType nor SequenceType. Now I know SequenceType requires the generate() method – but don’t let this fool you. CollectionType will provide that for you if you meet its requirements.

Take optionals, for example. Optionals demarcate when something’s not there at all. When an optional is nil, this may signify something went wrong. That’s much more explicit than relying on a convention like returning -1 for failed requests. This is convenient and changes the game of handling edge cases completely. Because whenever you receive an optional, you have to deal with its two-fold nature. Checking for -1 can slip your mind. Forgetting to unwrap an optional is unlikely.

All 3 amazingly useful objc.io books are 30% off this week. Grab all three of them in a bundle and save even more.

If you use my link, I’ll even get a small kickback thanks to their affiliate program. I wholeheartedly recommend you take at least the time to read the samples. The team updates their ebooks regularly, and you’ll get a Swift 3.0 edition later this year, too.

When parameter lists grow or two kinds of parameters seem to go together a lot, it’s time use the extract parameter object refactoring for greater good – then you can even specify sensible defaults.

This is a typical way to pass a set of options to an objects during initialization in a language like Swift. In languages like JavaScript or Ruby, dictionaries of key–value pairs can work just as well. Using dictionaries in Swift for this can be a pain, though.

Now Soroush wrote about a way that uses the Then microframework as a replacement for configuaration dictionaries. This way you don’t have to promote every property to the initializer’s list of parameters. Here’s a before and after, where you can see that without then you have to write a lot of repeating boilerplate:

// Before

struct FieldData {

let title: String

let placeholder: String

let keyboardType: UIKeyboardType

let secureEntry: Bool

let autocorrectType: UITextAutocorrectionType

let autocapitalizationType: UITextAutocapitalizationType

init(title: String,

placeholder: String = "",

keyboardType: UIKeyboardType = .Default,

secureEntry: Bool = false,

autocorrectType: UITextAutocorrectionType = .None,

autocapitalizationType: UITextAutocapitalizationType = .None)

{

self.title = title

self.placeholder = placeholder

self.keyboardType = keyboardType

self.secureEntry = secureEntry

self.autocorrectType = autocorrectType

self.autocapitalizationType = autocapitalizationType

}

}

let fieldData = FieldData(title: "Password", secureEntry: true)

Now with then, making non-mandatory properties mutable and getting rid of the boilerplate:

// After

struct FieldData {

let title: String

var placeholder = ""

var keyboardType = UIKeyboardType.Default

var secureEntry = false

var autocorrectType = UITextAutocorrectionType.No

var autocapitalizationType = UITextAutocapitalizationType.None

init(title: String) {

self.title = title

}

}

let fieldData = FieldData(title: "Password").then({

$0.secureEntry = true

})

That’s a Swift alternative to Ruby’s hash-based option initializers. There, the dictionary’s key is used as the setter’s name which is then invoked like so:

class Example

attr_reader :name, :age

def initialize(args)

args.each do |k,v|

instance_variable_set("@#{k}", v) unless v.nil?

end

end

end

e1 = Example.new :name => 'foo', :age => 33

#=> #<Example:0x3f9a1c @name="foo", @age=33>

Understanding Uncle Bob’s Principles of Object-Oriented Design (which resulted in the SOLID principles) is super important to really grasp the use of design patterns (like MVVM) and architectural patterns (like VIPER). It’s like the grammar for crafting proper object-oriented software.

And now here’s the good news: there is a Swift playground (and Markdown file to read online) that illustrates all the principles by Uncle Bob: The Principles of OOD in Swift 2.2

Check it out, take notes, and keep the principles close to your heart. They may save your life someday.

In “Creating a Cheap Protocol-Oriented Copy of SequenceType (with a Twist!)” I created my own indexedEnumerate() to return a special kind of enumeration: instead of a tuple of (Int, Element), I wanted to have a tuple of (Index, Element), where Index was a UInt starting at 1. A custom CollectionType can have a different type of index than Int, so I was quite disappointed that the default enumerate() simply returns a sequence with a counter for the elements at first.

Brent Simmons brings up valid concerns about the current state of Swift: you cannot write any software using Cocoa (AppKit for Mac or UIKit for iOS) with Swift without somehow interfacing with the Objective-C runtime. That’s kind of weird , don’t you think?

Daniel Jalkut of MarsEdit fame is slowly getting up to speed with Swift. I have a few Swift-only projects already (Move!, TableFlip and secret in-progress ones). On top of that, every feature I add to the Word Counter is a Swift module, too. The main code of the Word Counter is still in Objective-C, though.

Integrating new types to the project using Swift is awkward. There’re things you can only use in one direction. Most if not all Objective-C code can be made available for Swift and works great. The other way around, not so much. Also, Objective-C imports from the -Swift.h file won’t be available in Swift-based test targets. So you’ll have to isolate these even further, create wrappers, or whatever. Porting a class to Swift can work, but the side effects on testing make it harder.

I like Daniel’s advice to write your unit tests in Swift if you’re still not certain if you should make the switch to this new and volative language. It’s a good idea to get your feet wet.

Considering the problems I ran into with the Word Counter, though, I wouldn’t know how, honestly.

During the last weeks, I tried to use map() even when the conversion wasn’t straightforward to learn how it affects reading code. I found that some applications of map() were dumb while I liked how others turned out to read. The functional programming paradigm is about writing code in a declarative way, which has its benefits.

Here’s a guard statement with many different kinds of features by Benedikt Terhechte:

guard let messageids = overview.headers["message-id"],

messageid = messageids.first,

case .MessageId(_, let msgid) = messageid

where msgid == self.originalMessageID

else { return print("Unknown Message-ID:", overview) }

I love guard statements. It helps make code much more readable and keep methods un-intended.

I feel less amorous about guard-case and if-case matching, though:

if case .Fruit = foodType { ... }

This reads an awful lot like Yoda conditions where you place the constant portion on the left side. This isn’t even a typical boolean test (which would use the equality operator ==) but a failable assignment (=). I can force myself to read and write it this way, but it always feels backward to me. It took me quite a while to memorize this, which I found surprising, as it was comparatively easy to learn Swift in the first place.

Apart from the guard-case portion, the example contains your standard guard-let unwrapping. The else clause is special though, and I didn’t know this would work:

guard someCondition else { return print("a problem") }

When the function is of return type Void, you can return a call to another void function. This is shorter than splitting these two instructions on two lines, but it’s too clever for every reader to understand. print("a problem"); return is just as compact, as Terhechte points out.

Currying is a very useful and interesting thing. It means that you can write functions in parts. If you don’t provide all parts at once, you won’t get the “real” result but a closure that accepts the missing parameters. Like this, with spacing added to reveal how the nested closure maps to the chain of return types:

Although I knew there’s a “cookbook” book series, I haven’t read any of these before I read Erica Sadun’s The Swift Developer’s Handbook. The code listings are called “recipes”, and most of the time rightly so: I bet I copied about a dozen of the recipes into my own handy code snippet index to extend Swift’s capabilities with super useful things like safe Array indexes.

The gist of the article is that we can omit the verbose #selector syntax by adding a convenience property:

private extension Selector {

static let buttonTapped =

#selector(ViewController.buttonTapped(_:))

}

...

button.addTarget(self, action: .buttonTapped,

forControlEvents: .TouchUpInside)

I’d make that not private but internal and group these in a struct to separate them from other Selector stuff:

extension Selector {

// One for each view module ...

struct Banana {

static let changeSizeTapped =

#selector(BananaViewController.changeSizeTapped(_:))

}

struct Potato {

static let peelSelected =

#selector(PotatoViewController.peelSelected(_:))

}

}

// ...

button.addTarget(self, action: .Potato.peelSelected,

forControlEvents: .TouchUpInside)

Great tip!

When you implement CollectionType or SequenceType in custom types, you get a lot for free with just a few steps, like being able to use map on the collection. Any CollectionType implementation comes with enumerate() which, when you iterate over the result, wraps each element of the collection in a tuple with its index:

Did you know you can import only parts of a module? Found this in the Swiftz sample codes:

let xs = [1, 2, 0, 3, 4]

import protocol Swiftz.Semigroup

import func Swiftz.sconcat

import struct Swiftz.Min

//: The least element of a list can be had with the Min Semigroup.

let smallestElement = sconcat(Min(2), t: xs.map { Min($0) }).value() // 0

import protocol or even import func were very new to me. Handy!

Rethrows saves us a lot of duplicate code. Look at my naive approach to write an iterator in Swift 1 from last year which I later extended for throwing with Swift 2:

extension Array {

func each(@noescape iterator: (Element) -> Void) {

for element in self {

iterator(element)

}

}

func each(@noescape iterator: (Element) throws -> Void) throws {

for element in self {

try iterator(element)

}

}

}

This can be written as a single method with Swift 2 as I later found out:

extension Array {

func each(@noescape iterator: (Element) throws -> Void) rethrows {

for element in self {

try iterator(element)

}

}

}

The rethrows keyword makes the method a throwing one depending on the closure you pass in. Only if the closure throws each will throw, too. The compiler will know what happens – just like generic functions are write-once, use-many-times.

Of course I later found out that Swift 2 came with forEach already bundled in. So there’s no use in this anymore except for this very illustrative blog post to remember that throws/rethrows is different from throws/throws.

In a recent post, I wasn’t too fond of inline helper functions. Similar things can be accomplished with blocks instead of functions, as both are closures that capture their contexts. Blocks don’t even have to have a name. Inner functions and blocks share the same semantics. Found in Little Bites of Cocoa #180:

In Swift, you can define functions within functions. These are often referred to as helpers. Rob Napier brought this to my attention recently. Like any other closure, helper functions capture variables from their surrounding context if needed. This way you don’t have to pass them along as parameters.

The Word Counter is my biggest software project so far, and it’s growing. To add features, I discovered the use of Swift modules with joy. I can write code for all levels of the new feature in isolation in a new project that compiles fast. Later I plug the resulting project and module into the Word Counter, et voilà: feature finished.

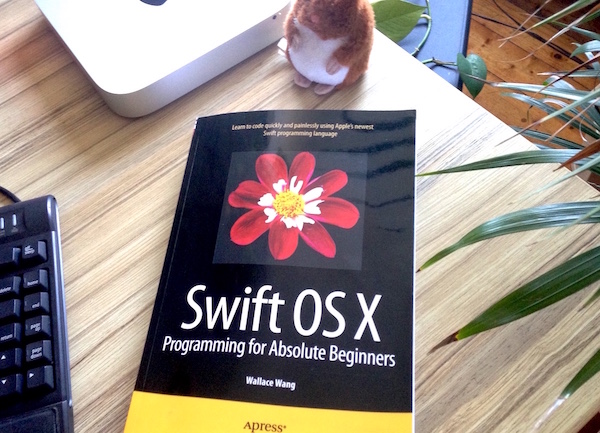

Recently on Google+, someone recommended Wallace Wang’s Swift OS X Programming for Absolute Beginners. Well, I’m not a beginner anymore, but the book sounded fun, so I gave it a spin. And I’m quite impressed. That’s why you read the review here. In short, Swift OS X Programming for Absolute Beginners (or SOXPAB as I would like to call it to save myself from typing that much) is the best programming book to teach the reader about user interface programming. I can’t honestly judge how well this textbook will actually work for non-programmers. But that’s because I can’t fathom learning to code from a book anyway. If you know programming, or the Cocoa APIs already, this should work for you.

So you miss declaring optional methods in Swift protocols? Joe Conway got you covered: “optional methods can be implemented by providing a default implementation in an extension.” But there’s an even better way, in my opinion: ditch the notion of optional methods and use blocks instead.

From the department of Domain-Driven Design code patterns, I today present to you: well-named value objects! You can go a lot farther than you have previously imagined with value objects in Swift. Now that Swift is more than a year old, most of us have seen the use of struct and heard how useful passing objects by value is.

I created a generic CoreDataFetchRequest a while ago and love it. It casts the results to the expected values or throws an error if something went wrong, which it shouldn’t ever, logically – but the Core Data API currently returns AnyObject everywhere, so I have to deal with that.

I found a very useful distinction by Matthijs Hollemans to grasp what protocol extensions in Swift 2 can be: instead of interfaces, they are traits or even mixins. At the same time, I want to raise awareness for misuse: just because behavior is mixed-in doesn’t mean it’s additional behavior. The code may live in another file, but its functionality can still clutter your objects.

I just found a shortcut to use Dependency Injection less during tests. In “Unit Testing in Swift 2.0”, Jorge Ortiz adapts solid testing principles to Swift. If you don’t have a strong testing background, make sure to watch his talk for key insights into the How using Swift!

I have just discovered how cool the new guard statement is to keep unit tests lean and shallow – avoiding if-let nesting, that is. Update 2021-05-11: Modern XCTUnwrap is even better. Consider this test case: There are two optionals I have to deal with. That’s why I throw in assertions to cover problems. I don’t want to assert anything new here, though: the test helper soleFile() is valdiated in another test case already. But I need some kind of failure in case the Core Data test case goes nuts.

Swift 2 brings a lot of Cocoa API changes. For one, Core Data’s NSManagedObject’s executeFetchRequest(_:) can throw, returns a non-optional on success, but still returns [AnyObject]. While refactoring existing code to use do-try-catch, I found the optional casting to [MyEntity] cumbersome.

I banged my head against Xcode’s wall (which is my computer screen) today, trying to find the source of an EXC_BAD_ACCESS code=2 termination. Turns out it’s the Swift 1.2 compiler which doesn’t catch a problem here. The signature of the block causing trouble with the version shown above:

Refactoring Legacy Code is hard. There are a few safe refactorings you can do with caution. But most chirurgical cuts require you to put the code in a test harness first to guard against regression. With C and Swift, you can create free functions as part of your app. To verify your objects use that function, you need to find a way to insert a test double.

I discovered a Swift library called Static the other day. It helps set up and fill UITableViews with static content – that is, it doesn’t permit deletion or rearrangement of new rows into the table. I think the following example to configure sections with rows reads really nice:

There’s this saying that the Strategy pattern can be realized in Swift using blocks. Without blocks, a Strategy object implements usually one required method of an interface (or protocol) to encapsulate a variation of behavior. This behavior can be switched at runtime. It’s like a plug-in.

Brent Simmons starts with Swift. And just as I, he struggles with value types, protocols, and generics: once a protocol references another or has a dependency on Self, you cannot use it as a type constraint or placeholder for all descending objects. You either have to use generics to expose a variant for each concrete type, or you re-write the protocol. There’s no equivalent to the way Objective-C did this: something like id<TheProtocol> just doesn’t exist. Swift is stricter. So how do you deal with that?

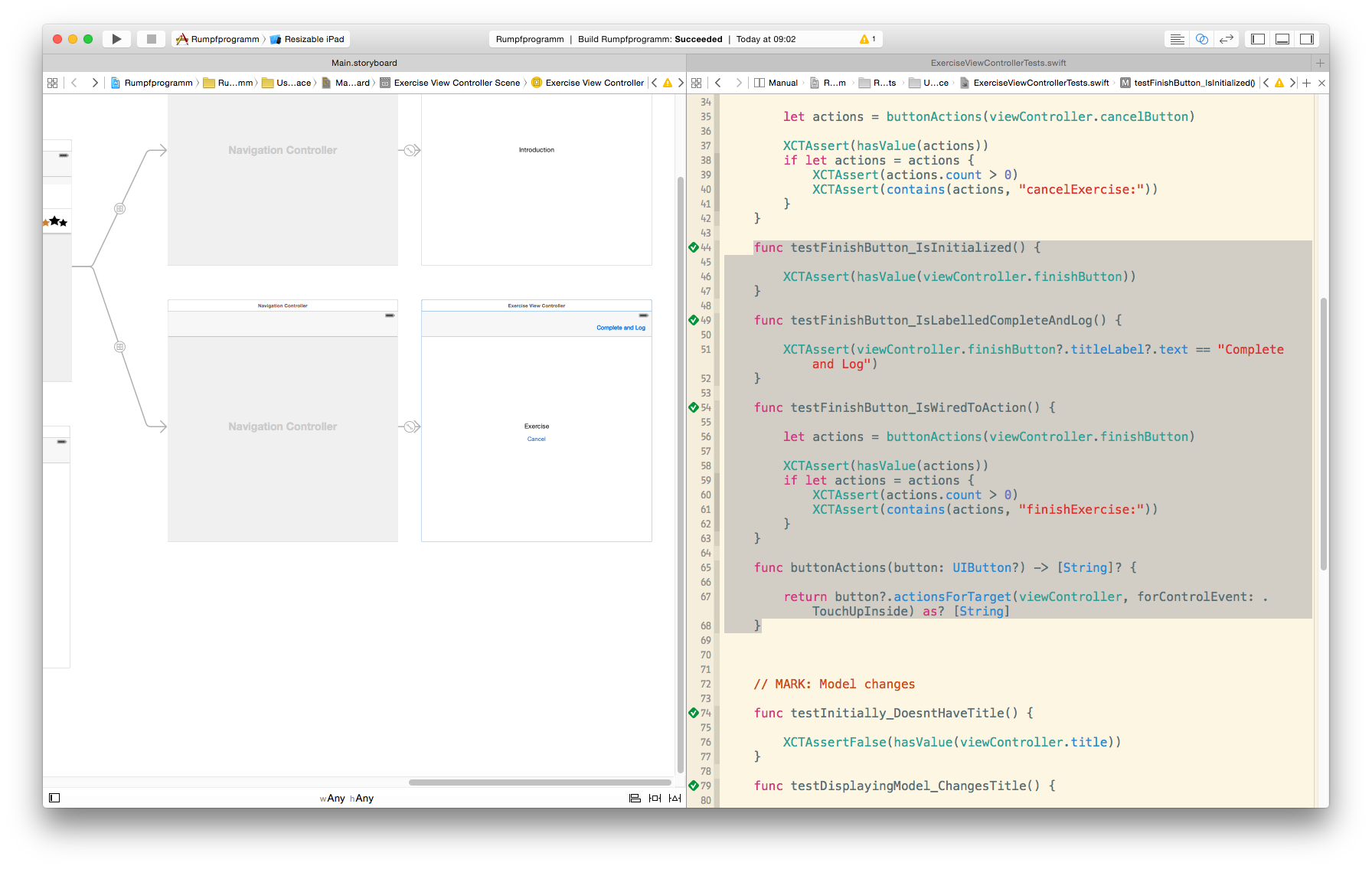

I’m writing unit tests for my Storyboard-based view controllers. Button interaction can be tested in view automation tests, but that’s slow, and it’s complicated, and it’s not even necessary for most cases. To write unit tests instead of UIAutomation tests for buttons, you test multiple things. Here are the tests.

I like when the code is explicit. Unlike Brent Simmons, I don’t feel comfortable using string literals in code especially not when I’m still fleshing things out and change values in Interface Builder a lot. In Objective-C, I would’ve used plain old constants. For storyboard segues, for example:

Throwing exceptions and being able to catch them is awesome news. Then there are cases which can be handled with try-catch technically, but shouldn’t. Think about this: in what cases could you make use of that? And what are the consequences for your work? For example, Erica Sadun points out that accessing array indexes out of bounds as a subscript will still crash the app since you can’t catch that kind of exception (yet).

You don’t have to learn anything new if you work with Core Data in Swift. It’s a pain to use NSManagedObject directly, so you better work with custom subclasses all the time. Unboxing optional NSNumbers is just too cumbersome. There are caveats you should be aware of, though: Swift’s static typing makes it a bit harder to write test doubles for managed objects.

Mocking and stubbing in tests is useful to verify behavior and replace collaborating objects with simpler alternatives. Since Swift is statically typed, you can’t use a mocking library anymore. But it’s trivially simple to write simple mock objects as subclasses in place:

Until today, I had a regular-looking “fetch all” method on a Repository I am working with. It obtains all records from Core Data. When I discovered the nice Result enum by Rob Rix, things changed. I talked about using a Result enum before, but haven’t used an implementation with so many cool additions.

Swift 1.2 brought very nice additions to the functionality of the language. Among one of my favorites is that we can now use Key-Value Observing on enum attributes. Here’s an example. Capacities of container are pre-set in our domain, so it makes sense to create an enum to represent the allowed values:

Andrew Bancroft tested and analyzed the behavior of extensions in Swift. While his findings aren’t utterly surprising, having them summed up in this nicely done article certainly helps.

In a nutshell:

privat members (attributes and methods, that is)internal and public members – but only if they are in the same modulepublic memberspublic or internal visibility on themselves expose their members as internal by defaultprivate visibility on themselves expose their members as privatepublic for public members to work (unlike classes)This has consequences for your tests: they reside in a separate module, so they can only access public members of your classes.

If you extend classes from static libraries, the same holds true. Different module, only public accessors.

I’ve written about using the Result enum to return values or errors already. Result guards against errors in the process. There’s also a way to guard against latency, often called “Futures”. There exist well-crafted solutions in Swift already.

After the latest change in my diet, I eat a lot more often throughout the day and try to spend the time watching educational talks to make use of my time. Functional programming seems to not only be all the hype – its concepts seem to reach mainstream thinking, too. Here’s a collection of talks you might find worth your while.

If you got some useful talks, share them in the comments!

Erica Sadun brought up a topic which is bugging me for some time already. It’s how Swift encourages you to handle optionals. It’s related to handling exceptions, which I covered earlier. Either you use if-let to unwrap them implicitly and do all the stuff inside the nested code block, or you end up with code which is a lot wordier than I’d like it to be.

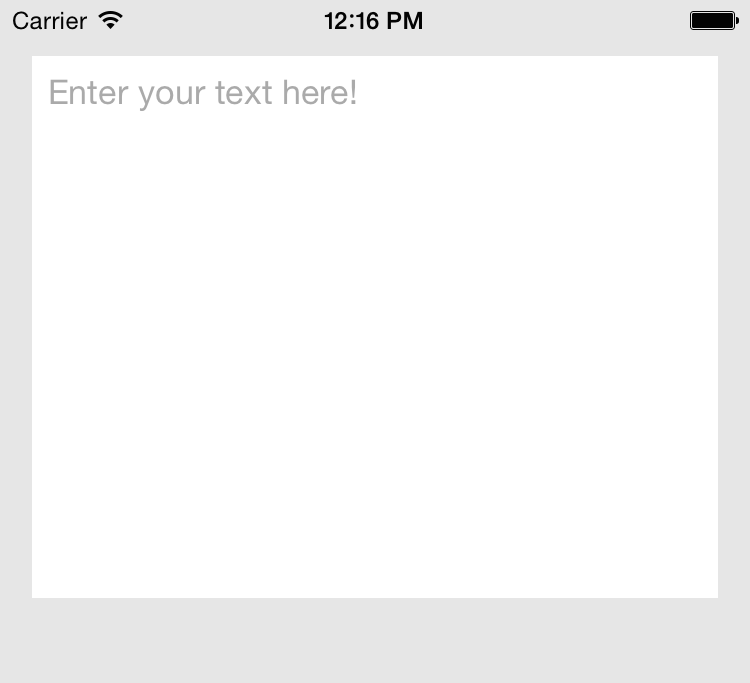

Kevin McNeish created a Swift extension for UITextView to show a placeholder text when a text field is still empty. It takes all the burden from the view controller and is a real plug-in: it won’t interfere with existing code and only requires you add the file to your project. That’s it.

In Swift, there’s no exception handling or throwing. If you can’t use exceptions for control flow like you would in Java, what else are you going to do if you (a) write library code which executes a failing subroutine, and (b) you find unwrapping optionals too cumbersome? I played with the thought of keeping Swift code clean, avoiding the use of optionals, while maintaining their intent to communicate failing operations.

Chris Eidhof provided an excellent example for creating a mini Swift networking library. It executes simple requests and can be extended to work with JSON (or XML, if you must) without any change. The accompanying talk is worth watching, too. You should check it out to see well-factored Swift code in action. It’s a great example.